A Guide

to the Charles Alling Diary

Below is an alphabetical listing of people, events, terms, etc.

found in Charles Alling's diary. Students from His234

Studies in American Cultural History: The Middle Class, taught by Sarah McNair Vosmeier (2009

to 2014) provided this background information and contributed to the transcription

of the diary.

The original diary is available at the Duggan

Library Archives, Hanover College (Hanover, Ind.).

Alling, Charles, Jr.

[volunteer needed to give background from finding aid]

Charles Alling, Sr. was a hardware merchant and raised

eight children.

Source: Tenth Census, 1880, Hanover, Jefferson

County, Indiana, series T9, roll 287, p. 147, s.v. Charles Alling,

--- research by Meghan Cooper and Tiffanie Patton, HC

2012

Rob is short for Robinson, who was ten years old in 1883.

Source: Tenth Census, 1880, Hanover, Jefferson County, Indiana,

series T9, roll 287, p. 147, s.v. Charles Alling.

-- research by Sarah Helms, HC 2012

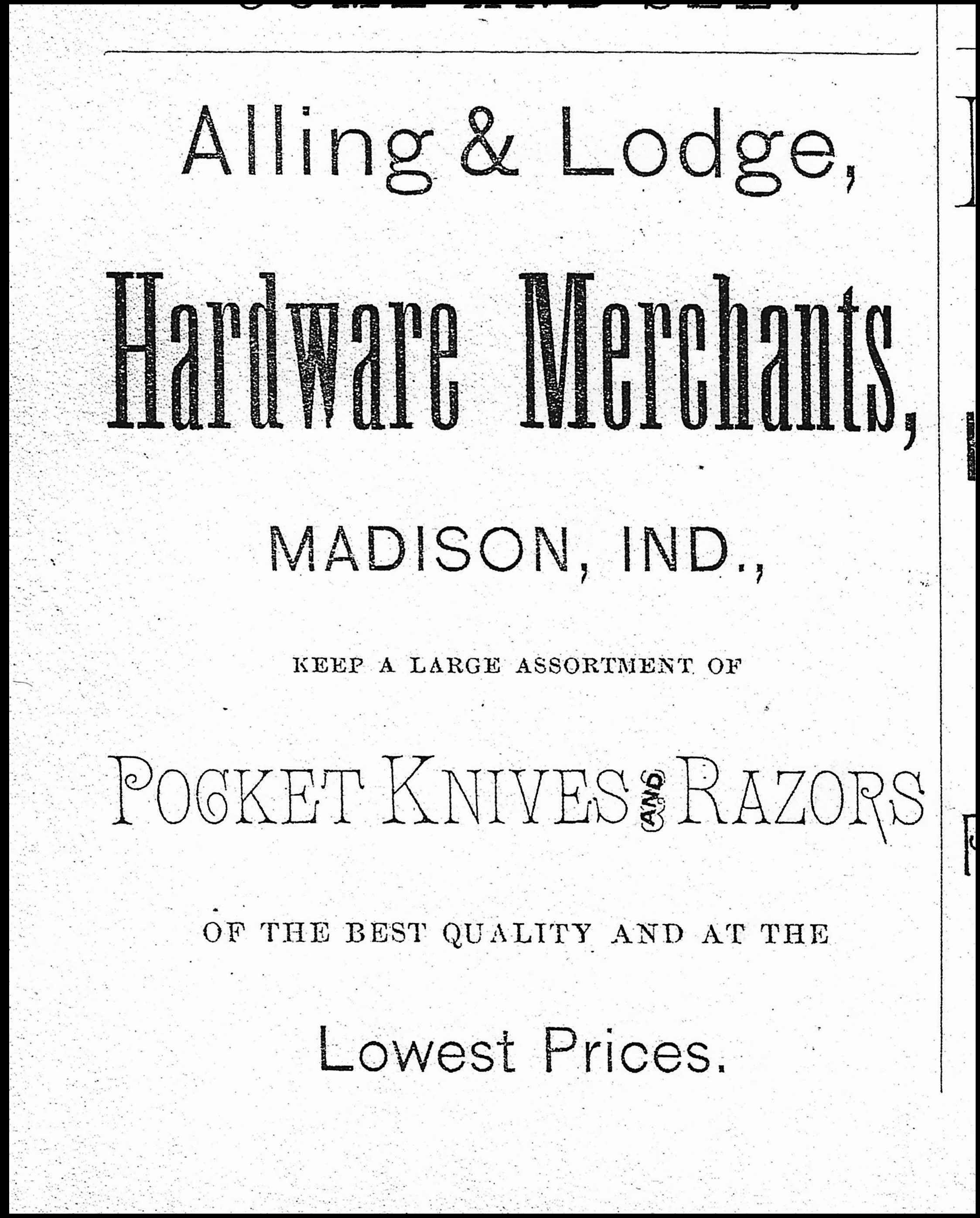

| Alling and Lodge Hardware Co |

The hardware store was located at 118 East Main Street in downtown Madison,

Indiana. At this time, it was owned by Alling's father, Charles Alling

senior, and his partner, Gavin Lodge.

Source: Ron Grimes and Bob Thomas, Jefferson County

Historical Society volunteers, conversation with author, 22 Sep. 2010.

-- Brandon Doub, HC 2013

In his journal entries Charles Alling makes reference to many individuals

with whom he associated. One such individual is William Martyn Baird, or

Baird as Alling called him. William Baird was eighteen at the time of the

1880 census. He grew up in Charlestown, Indiana, twenty-six miles south-west

of Hanover. His father, John Baird, was a farmer and his mother, Nancy

Baird, was listed as a housekeeper. William lived with his father, mother

and three siblings: John F. Baird (older brother), Marry, and Ann (older

sisters). As one can see, William was the youngest of four children.

William came from a working-class family with middle-class ideals and

aspirations. Even though his father earned his wages through tough manual

labor, he still believed in seeking out higher education for his children.

In the late 1800s, the national college attendance rate was less than five

percent. So, for a farming man to want to send his son to college is a

mark of growing middle-class values. Even John F. Baird, William's

brother, was a teacher. William could be classified into the outsider

sub-culture of college life in the late 1800s. For one, he is not wealthy.

The majority of those in the participant sub-culture come from wealthy

families, and they are not in college to learn from the professors, but to

gain more connections made in college with peers. In Alling's journal

entry whenever he mentions Baird, the pair of them and a few other friends

are either studying or reading. So, as one can see, he is focused on his

studies more than extracurricular activities like intramural sports.

However, both Alling and Baird were well-known on campus for their

orations. One can view this as extracurricular, but one can also view this

as an educational exercise, as public speaking is an art that every

successful person must master. This is the reasoning behind placing Baird

in the outsider sub-culture.

William's brother, John F. Baird, was employed as a teacher at the time

of the census. At the time of William's attendance at Hanover College, he

was on the faculty. John was twenty-eight in 1880, making him thirty-one

in 1883. It was common practice to attend college to pursue a future in

the Church; this would explain the Rev. title given to John. In October,

1877, John F. Baird presented Vol. 1 No.1 of the Hanover College

Monthly. Hanover College Monthly was one of many campus

newspapers that were started in the late 1800s. Others include: The

Hanoverian (1880), The Bohemian (1882-1883), and The

Journal of Hanover College (1894). John F. Baird was involved in

spurring on many literary publications on Hanover's campus in the late

nineteenth century.

Sources: 1880 United States Census, s.v. William Martyn Baird, Hanover,

Jefferson County, Indiana, accessed through Ancestry.com; Sarah M.

Vosmeier, lectures for American Cultural History: Middle Class, Hanover

College, 29 September 2014, 9 September 2014; Hannah Clore, Charles

Alling, Jr., Diary, Sunday, May 25, 1884, in Notes

on the Charles Alling Diary (accessed 30 Sept. 2014); William

Alfred Millis, The History of Hanover College From 1827 to 1927

(Hanover, Indiana: Hanover College, 1927), 242, Hanover

Historical Texts Collection (accessed 30 Sept. 2014).

-- Matthew Todd, HC 2016

Census and land ownership records indicate that Miss Lottie, or Lotta

Brewer was the daughter of Samuel Brewer, a printer living in the 4th

Ward. The Brewers resided at 509 West Street. Lotta Brewer is seventeen

years old when she is referenced in this passage.

Source: Ron Grimes and Bob Thomas, Jefferson County

Historical Society volunteers, conversation with author, 22 Sep. 2010;

U.S. Department of the Interior, Census Office, Tenth Census, 1880,

Hanover, Jefferson County, Indiana, s.v. Samuel Brewer, Heritage Quest,

HeritageQuestOnline.com.

-- Brandon Doub, HC 2013

A middle class value that Alling embodies is his care for his appearance.

The Dec. 28, 1883, diary entry shows that he cares about the condition

of his clothes -- he wants to look clean. This is a quality that Rev. John

Todd discusses in The Student Manual. Rev. John Todd talks

about dressing neatly and cleanliness in general and its importance in

society as a gentleman. Readers could also take this as meaning that

this may be one of his only outfits, and therefore he really needs to keep

it in good condition. Alling's entry also emphasizes that he is

hard-working.

Source: John Todd, The Student Manual (Northampton:

J. H. Butler, 1835).

-- Kelsey Weihe, HC 2014

After transcribing the diary entry of Charles Alling, Alling made mention of

a man named Rev. Mr. DeWitt of Lane Theological Seminary. According to

Alling, this man came and preached about Christianity to the young men of

Hanover College. Reverend DeWitt was born October 10, 1842, in Harrisburg,

Pennsylvania. DeWitt went to the College of New Jersey, which is now called

Princeton University. Information from Princeton Theological seminary states

that DeWitt was enrolled in college from 1861 until 1863. After college,

DeWitt followed the path of ministry. He was ordained as a pastor the summer

of 1865 at the Third Presbyterian Church in New York City. During the years

of 1865 until 1882, DeWitt preached at several churches. Over the span of

seventeen years, DeWitt preached in three different locations: New York,

Massachusetts, and Philadelphia. During his time as a pastor, he was granted

the Doctor of Divinity from the College of New Jersey in 1877. After years

of being a pastor, DeWitt made a change in profession. In 1882 he became a

professor of Church History at Lane Theological Seminary. During his time at

Lane Theological Seminary he made a visit to Hanover College. In the year of

1888 Hanover College presented DeWitt with a Doctrine of Law. After this

award, DeWitt switched schools and went to teach at McCormick Theological

Seminary, where he was a professor of Apologetics.

At McCormick Theological Seminary, John DeWitt became a well-known

professor. The salary that DeWitt earned while working at the college can

be found in the book, A History of the McCormick Theological Seminary

of the Presbyterian Church. It states that he earned three thousand

dollars per year. In addition to his salary, he was provided with a place

to live on the seminary grounds like the other professors. Reverend DeWitt

stayed with the McCormick Theological Seminary until 1892. In 1892 DeWitt

went back to where his schooling all started, Princeton Theological

Seminary. By this time, the school actually went by Princeton instead of

College of New Jersey. While at Princeton, he was a professor of Church

History again and also served as a trustee. DeWitt was a professor until

1912; he then lived his life out in Princeton, New Jersey, until his death

on November 23, 1923.

Reverend DeWitt lived a busy life and seemed to be a successful man. He

was able to move around multiple times and recognized for his success by

two different colleges, one which was Hanover College. John DeWitt not

only left an impression on Charles Alling, but on many others over the

course of his life as well.

Sources: Leroy Jones Halsey, A History of the McCormick

Theological Seminary of the Presbyterian Church, 1893 (University of

California, 2007), pg 439-440 (accessed online);

Special Collections staff, Princeton Theological Libraries, The John

DeWitt Manuscript Collection Summary, 1881-1910, Princeton Theological

Seminary, New Jersey (accessed online,

Sept. 26, 2014).

-- Amelia Facemire, HC 2015

Daniel Webster Fisher is often referred to as D.W.

Fisher. Fisher began his career at Hanover as a Holliday Prof. of

Logic and Mental Philosophy and Crowe Memorial Prof. of Biblical

Instruction, but his s impact on Hanover College did not end with

teaching. He became president of the college in 1879, ending his

term in 1907.

Sources: Hanover Monthly: From 1883.-84.-85. (Hanover

College); Hanover College History, Hanover College: Duggan

Library, http://library.hanover.edu/archives/hchistory.php (accessed 24

Sept. 2012);

-- Emily Fehr, HC 2013

Dr. Daniel Fisher was born on January 17, 1838, in Arch

Spring, Pennsylvania. He coincidentally graduated from Jefferson College

(Hanover is in Jefferson County) in Pennsylvania and studied theology.

He pastored numerous churches throughout his career including Second

Presbyterian Church in Madison, Indiana, which is just outside of

Hanover. According to The National Cyclopedia of American Biography,

his presidency included many challenges; he eliminated the college's

debt, increased the endowment, and improved the college's reputation

among churches and friends of the college. At the time of his

retirement, the college's endowment was $200,000, and the property and

buildings were worth $150,000.

Annual Catalog of Hanover College 1884; Lyman Abbott and others,

The National Cyclopedia of American Biography (James T. White and

Company, 1891), II, 125.

-- Jared Gluff, HC 2011

We learned from Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz that the

student-professor relationship was often a hostile one. We do not hear

much of students taking an interest in getting to know their professors on

a personal level as Alling does. One explanation that did cross my

mind while investigating this mystery in the archives was that Dr. Fisher

had a son named Howard who was the same age as Alling. If Charles Alling

was close to Howard Fisher, he would probably know his father very well as

well.

Source: Helen L. Horowitz, Campus Life:

Undergraduate Cultures from the End of the Eighteenth Century to the

Present (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1987),

23-55, 193-219.

-- Michael Gilliam, HC 2011

Edith Fisher is signified as being a sophomore at Hanover College during

the 1884-85 academic year. Edith is listed as having been one of the few

that took Special courses compared to the traditional Scientific or

Classical courses.

Source: Edith Fisher, The Alumni Record, in Bulletin

Hanover College, ed. Joshua Bolles Garritt et al, Vol. V, No. 11,

March 1, 1913.

-- Brandon Doub, HC 2013

Graham, Alexander and Jennie

|

Alexander Graham was the same age as Charles Alling, eighteen years old, in

1884. He lived in Madison, Indiana, in 1880. Jen is probably Jennie Graham,

his sister.

Source: Tenth Census, 1880, Hanover, Jefferson County, Indiana,

series T9, roll 287, p. 153, s.v. Alexander Graham, Jennie Graham.

-- research by Tiffanie Patton, HC

2012.

The 1884 Hanover Monthly includes an advertisement encouraging

people to enroll in the upcoming semester, noting that Hanover accepted

both sexes and promoting the two tracks offered: Classical and Scientific.

Tuition was free, boarding ranged from $2.75 to $3.50 per week, and other

expenditures ranged from $40 to $60, totaling no more than $175 to $200

per semester. The Hanover College Timeline gives a sense

of what Hanover was like in the 1880s. The first thing that caught my

attention was that women were not admitted to full privileges as students

at Hanover College until September of 1880. The next event that

struck me was the charter of Kappa Alpha Theta on campus on January 2,

1882. The first fraternity at Hanover was established in 1853, only

29 years before the arrival of a sorority on campus. Calla Harrison,

the first woman of Hanover College, graduated in 1883. Finally, the

Department of Music and Art was not established until 1887.

Sources: Hanover Monthly: From 1883.-84.-85.

(Hanover College); Hanover College History, Hanover College:

Duggan Library, http://library.hanover.edu/archives/hchistory.php

(accessed 24 Sept. 2012); Annual Catalog of Hanover College 1884 (Hanover

College: Duggan Library); Sarah McNair Vosmeier, lecture for Studies

in American Cultural History: The Middle Class, 19 September 2012.

-- Emily Fehr, HC 2013

.

Hanover College, Class of 1885

|

Charles Alling's junior class in 1884 had nineteen students,

including Alling. Based on the names of the students, it is reasonable to

assume Alling's class was composed solely of males. Thus, it is fair to

assume that at this time it was rare, if it happened at all, for a woman

to attend school at Hanover. Sixteen students out of Alling's class were

either from Hanover or neighboring towns in Indiana. Only three students

were from out of state. Out of the students from Indiana, four were from

Madison, one was from Charleston, one was from Franklin, one was from

Vernon, three were locals from Hanover, one was from Greensburg, two from

Vevay, one from Seymour, and finally one from Deputy, Indiana. The three

from out of state were from Nicholasville, Ohio; New Liberty, Kentucky;

and Chilocothe, Ohio. Hence, due to the class ratio from local Indiana

students and students from out of state, and due to the difficulty and

expense of travel, one can make the inference that it was difficult for

students from a considerable distance to get to Hanover or even hear about

it.

Sources: Annual Catalog of Hanover College, Hanover

College Archives, 1833-present, April of 1884, Frank S. Baker, Glimpses

of Hanover's Past, 1827-1977. [s.l.]: Graessle-Mercer Co., 1978.

-- Amber Carrell, HC 2010

Hanover College,

curriculum (1883)

|

In these two entries from Alling's diary, he makes mention of some of

the classes and projects he was involved in during his junior year at

Hanover College. What is of interest is how the freshmen are required to

read Livy and how he himself must study Latin while simultaneously taking

chemistry and political science classes. While it may just seem like

Alling is fulfilling the tradition of a liberal education at Hanover

College, his academic curriculum while attending Hanover College was

mirrored all around the United States roughly around the late nineteenth

century.

A look at the Hanover Catalogue from this time shows a strictly

structured academic career planned out from freshman year to senior year.

Yet, there was a heavy emphasis placed on a classics education at the

commencement of their college career. First-year students were expected to

study the ancient works of Livy, Xenophon, Horace, and Homer, with barely

any classes geared towards the sciences, mathematics, or theology. The

emphasis on the classics in colleges and universities in the United States

during this time harkened back to the European ideology that knowledge was

a fixed body that was meant to exercise reason, memory, imagination,

judgment, and attention in the student.

Carol Gruber also argues that such a definition of higher education was

more reflective of that needed to enter the clergy, an older profession

which was one of few career paths that actually required higher education.

To err away from the generally agreed upon body of knowledge was not

necessary for an educated man who sought to enter the clergy because there

was little point in deviating from a tried and true method to mold the

future men of the church. The late nineteenth century was a time of

change, though, and academia had begun to shift their understanding of

higher studies into a form that modern students could more easily

identify. This shift created an emphasis on not just the classics and

theology but towards the sciences and mathematics sometime in the 1870s

after European universities and colleges experienced their own overhaul of

traditional educations to accommodate new interests and careers. Thus, it

is not strange for Alling to write about classes that deal more with the

sciences as Hanover College was experiencing this transition to a new

definition of what was an acceptable education.

In fact, the Hanover Catalogue also reflects this shift in the

importance of higher studies. Although the early years of a nineteenth

century student's academic career would be bogged down with courses based

on a classics' education, by their junior and senior years, they began to

have more options in different areas of studies. By their senior year,

there are more classes centered on the sciences, theology, and

mathematics, than any classes for Greek or Latin. It is very much possible

that this would have been the last year that Alling would need to study

his Latin seriously at all.

Sources: Catalogue of Hanover College, Indiana, Archives of

Hanover College, Duggan Library, Hanover College (Hanover, Ind.); Carol

Gruber, Backdrop, The History of Higher Education (Boston 1997:

Pearson Custom Publishing), 203, 204.

-- Ivana Eiler, HC 2015

Hanover College, College Point House

|

The College Point House existed where the Administration

building sits now (in 2009), adjacent to the Fiji fraternity house and

College House. The Point House was built obviously prior to 1884, and

lasted until it was torn down in 1958 during the year that also marked the

end of Albert Charles Parker, Jr.'s term as president at Hanover College

and marked the beginning of John Edward Horner's term as president. The

Point House began as an all-male dormitory, but as a few students fondly

remember, it became a controversial co-ed dorm before it was destroyed in

1958.

Sources: Annual Catalog of Hanover College, Hanover

College Archives, 1833-present, April of 1884, Frank S. Baker, Glimpses

of Hanover's Past, 1827-1977. [s.l.]: Graessle-Mercer Co., 1978.

-- Amber Carrell, HC 2010

Hanover College,

Presbyterian affiliation

|

In Allings diary of September 16, 1883, he mentions that all of the men

of the college are required to attend Sunday School. He states that

Professor Garritt and Professor Fisher are the leaders of the Sermon.

During their sermon that day, they gave a lesson on the first of Samuel.

He says that they also mention Proverbs 1:10, quoting Consent not, my son,

where sinners entice thee.

Many college campuses during this time period were

religiously-affiliated. In Allings case at Hanover College, the

affiliation was Presbyterian. According to Mary Brown Bullock, the

Presbyterian and Reformed tradition shaped the nature of American higher

education in the 19th century, especially the culture and mission of

liberal arts colleges. Princeton University, founded in 1746, was the

first college with ties to the Presbyterian religion. John Witherspoon

brought the ideas of the Scottish Reformed educational tradition to the

school, and then these values spread to the rest of the country. These

values included the importance of both faith and knowledge, a Christian

sense of vocation, the idea that a college campus should be the center for

morality, as well as the notion that college students should be preparing

for a life of service to the world (Bullock).

Specifically, the combination of Presbyterianism and a liberal arts

college, like Hanover, was formed to emphasize educating for a life beyond

self, beyond pure knowledge, its emphasis on character and on the full

human potentiality of all persons (Bullock). These values, which existed

as the founding philosophy for liberal arts schools, still exist today. In

the case of Hanover College, the Hanover Presbyterian Churchs pastor

founded the school, largely supported by the church's officers and

members. The most prominent elder of the congregation, Judge Williamson

Dunn, donated time, land, and money for the founding of the college

(Millis). Without the Presbyterian Church of Hanover, there would be no

Hanover College.

Although from 1836-1837, the catalogue of Indiana Theological Seminary

and Hanover College provides a general schedule of theological instruction

at Hanover College in the 19th century. The students were divided by year

as Juniors, Middle, and Seniors. Terms were eight months, from November to

June. At the end of each term, the Juniors and Middle class were

publically examined on their term information. Seniors were examined on

the term information from all three terms. Students were expected to learn

the subjects of Scriptures, Biblical Literature, Archeology, and

Hermeneutics. With the Professor of Ecclesiastical History, to Sacred

Chronology, Biblical History, Church Government, and the Composition and

Delivery of Sermons as well as Mental and Moral Philosophy, Natural and

Revealed Religion, didactic, Polemic, and Pastoral Theology (Millis).

Sources: Mary Brown Bullock, The Birthright of Our Tradition: The

Presbyterian Mission to Higher Educatio, The Presbyterian Outlook,

2002 (accessed online);

William Alfred Millis. The History of Hanover College From 1827 to

1927 (Hanover, Indiana: Hanover College, 1927), 79-91 (accessed online).

-- Mina Enk, HC 2015

Hanover College, Spring

Exhibition

|

The Spring Exhibitions were speeches that were given over the course of

several days. One example was a speech delivered during the Spring

Exhibition of March 25, 1863, by a man named John Holliday, a student at

Hanover College at the time. This particular speech discussed the Civil War

and hatred toward slavery. These exhibitions probably would have been very

popular amongst the students at Hanover College because their own peers gave

some of the speeches, as well as some guest speakers.

Source: John Holliday, Conservatists

in Hanover

Historical Review 7 (1999).

-- Michael Gilliam, HC 2011

Florence Harper was seventeen years old in 1884 and lived in Madison,

Indiana, in 1880 (at 412 West Third Street). Her parents were Fred and

Emily Harper, and her father was a prescription clerk who worked at the

northwest corner of Main and Jefferson Streets. She had four sisters and

one brother.

Source: Tenth Census, 1880, Hanover, Jefferson County, Indiana,

series T9, roll 287, p. 118, s.v. Florence Harper; Ron Grimes and Bob

Thomas, Jefferson County Historical Society volunteers, conversation with

Brandon Doub, 22 Sep. 2010.

-- research by Brandon Doub, HC 2013, and Tiffanie Patton,

HC 2012.

In Alling's journal from the nineteenth century, there is a mention from

the passage transcribed of a girl named Florence Harper. As she is

mentioned once as a potential friend that Alling had at Hanover College,

she became interesting as a potential woman who received a higher

education in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Thus, I will be

examining the education common for women in the second half of the

nineteenth century and specifically what was expected of them. There is no

evidence of Florence or any of her siblings attending Hanover College,

suggesting she was merely a local girl who came for visits. However, there

is an interest in the education that a girl of her status was likely to

receive in her time and space.

To begin with, Florence Harper was the second youngest of six children

by a Fred Harper, a druggist in Madison, Indiana. Her mother is listed as

a keeper of the house, but what especially snags the interest is the

addition of one aunt with a separate last name, who is listed as a

schoolteacher. Furthermore, the aunt is unmarried but living with her

brother-in-law and her sister. Teaching as a career for women was

interesting, as again there was no evidence of the aunt attending Hanover

College4. Thus, the fact she is living with her sister could suggest that

she is underpaid or simply lonely. Teaching in Madison would suggest that

the aunt had at least some rudimentary education to draw on. The education

ubiquitous to women in the second half of the nineteenth century (after

1850) and the cultural significance of women became interesting.

An article by Arthur D. Elfland offered an idea of how women were

educated and how their education advanced in the nineteenth century.

Elfland focuses chiefly on art as a vehicle of female education, as women

who were accomplished in art were seen to be the epitome of female

morality. While his main focus centers on art, there was also a

considerable amount of evidence regarding the growth of education in

Boston for young women. The primary reason behind a woman's education

prior to the latter half of the nineteenth century was to find a husband6.

However, with increasing numbers, women were beginning to enter the

teaching profession, just as Florence's aunt did in Madison, Indiana. As

the demand for teachers grew, education for women became a necessity.

Therefore, schools became much more interested in educating people

outside of the rich and privileged upper classes, as had been the case

before with the case of drawing. Since the main form of schools in America

at the time for women were private schools, new formations of schools such

as high schools began, which could offer education to the working or

middle classes. Curriculums offered at these schools came to mirror that

of the elite privates schools, mostly due to the educated young women who

were now teaching. As with many societies, those of the working class

often found themselves with little money or little reason to send their

children to school, in sharp contrast with the middle class, which valued

the potential education of their children. Teaching remained the main

drive behind young, middle class women attending schools, as it was the

main career a girl could aspire to.

It is unknown whether or not Florence Harper's aunt was one of these

women with a certain 'moral character' that was required to be a teacher

in the nineteenth century. Since Elfland's article is primarily limited to

the women living in and around Boston after 1852, it is hard to determine

whether or not a woman in Madison, Indiana, would have received a similar

education. It is hard to imagine, as Florence's aunt was living in

southern Indiana with her brother-in-law and sister. Women in the

nineteenth century were beginning to receive more and more education,

which is quite apparent with Elfland's article and the rise of the middle

class. The factors associated with the further education of women suggest

a growing need to educate both genders, rather than leaving education and

knowledge up to the men. One could speculate that perhaps Florence herself

followed a path similar to her aunt and attended a college other than

Hanover. It is likely that she married someone and became a housewife like

her mother as well. But it is an undeniable fact that the education of

women was slowly morphing into system that could be equal to male

education.

Sources: 1880 United States Census, s.v. Florence Harper,

Hanover, Jefferson County, Indiana, accessed through Ancestry.com; Arthur

D. Elfland, Art and Education For Women in 19th Century Boston, Studies

in Art Education 26, no. 3 (1985). 133-140; Catalogue of Hanover

College, Indiana, Archives of Hanover College, Duggan Library, Hanover

College (Hanover, Ind.).

-- Annabelle Goshorn-Maroney,

HC 2015

Census and land ownership records indicate that a George Kimmel lived just a

few blocks away from the Alling residence located at 519 Main Street, now

named Jefferson Street. Mr. Kimmel, a brick maker by trade, resided at 912

Walnut Street on a plot of land that spanned beyond city limits. Mr. George

Kimmel's particular property and a stone quarry, ever-so conveniently, were

located just off of Crooked Creek. Local historians recount a number of

small ponds that had sustained by the creek for various reasons or another

on the outskirts of the 3rd ward. Sadly, they report that most all of them

have been filled in and built upon over the last sixty to eighty years.

Source: Ron Grimes and Bob Thomas, Jefferson County

Historical Society volunteers, conversation with author, 22 Sep. 2010.

-- Brandon Doub, HC 2013

Lepper, Lilly, and Daisy

Lepper

|

Census records indicate the Lepper girls mentioned were the daughters of Mr.

and Mrs. William and Mary Lepper. The girls, Lilly and Daisy, were sixteen

and twelve years of age, respectively, at the time of the entry.

Source: U.S. Department of the Interior, Census Office, Tenth

Census, 1880, Hanover, Jefferson County, Indiana, s.v. William C. Lepper,

Heritage Quest, HeritageQuestOnline.com.

-- Brandon Doub, HC 2013

.

More on this story is here: Poet's

Corner: The Mistletoe Bough, (accessed 26 September 2010).

-- Meghan Cooper

Mr. John B. McCoy was a Baptist preacher in the Hanover area, possibly at

the college itself. In the census of 1880 he was 34 years old and had a wife

named Lizzie, but had no children.

Source: U.S. Department of the Interior, Census Office, Tenth

Census, 1880, Madison, Jefferson County, Indiana, series T9, roll 287, p.

28.

-- Jennifer Wullenweber,

HC 2012

Moore's Hill College was a college founded in the small town of Moores

Hill in southeastern Indiana, not too far northeast of Madison, Indiana in

Dearborn County. Opening in 1854, Moores Hill College remained in Moores

Hill until 1917 when it closed its doors to make the move to Evansville,

Indiana. Moores Hill College reopened its doors in 1919 under the new name

of Evansville College. Today, some 156 years later, the legacy of Moores

Hill College lives on through what is now known as the University of

Evansville.

Source: History,

University of Evansville, (accessed 25 Sep. 2010).

-- Brandon Doub, HC 2013

Nathan Powell was born in Madison, Indiana. After graduating from Hanover

College in 1884, he studied law at Johns Hopkins University and Harvard

University.

Source: Alumni File of Nathan Powell, Class 1884, Archives of

Hanover College, Duggan Library, Hanover College, (Hanover, Indiana).

-- Jake Cummins, HC 2012

Since the existence of money, its value as a resource has been on an

ever-changing cycle. I remember hearing stories from my grandparents of

particular purchases they made when they were younger, and I would be in awe

of how cheap it sounded to me. As I transcribed Charles Alling's diary, I

was once again reminded of how the value of money changes over time. For

example, Alling mentioned in his journal about a friend offering to buy his

desk for $5.00, and making a profit of $3.50 if he was to sell it.

Additionally, he talked about purchasing some books that were worth $8.25,

and the fact that the farther he advanced in college, the more expensive his

books were becoming. Upon reading this, I became interested in the economy

of the 1883 time period, and exactly what the worth of a dollar was at that

time.

First, I felt it important to cover what contributes to the change of

money's value. Scott Derks, author of The Value of A Dollar: 1860-1999

(1999), stated that a particular item in any given year has potential to

be sold at different prices depending on three factors: availability

(amount of supply), demand of the consumer, and/or the retailer's need for

cash. Moreover, within the same city, the price of an item may vary

depending on the cost of inventory, overhead, competition between

businesses, demographics of the retailer's consumer base, holiday sales

advertising, cash flow, or simply the inclination of the owner. The

consumer plays a significant role to the value of a dollar, as well. The

majority of consumers do not make personal economic choices based on

ratios, the latest craze, and models. More often than not, a consumer's

buying choice will be strongly based on options and what takes priority.1

For example, one would more than likely make the choice to pay the monthly

water bill over buying a new pair of shoes.

As a student at Hanover in 1883 (along with most students in the present

day), Charles Alling probably made several financial decisions during his

college term; perhaps some responsible and some not. However, the value of

a dollar during this time period is quite different than today. Based on

the composite consumer price index of 1860, the dollar's worth was exactly

$1.00. Due to inflation or deflation, a dollar's worth can increase or

decrease. By 1883, it took $1.21 to buy one dollar's worth of 1860's

goods.2 Today, it would take approximately $23.63 to purchase one dollar's

worth of 1860's goods.3 So, if Alling would have sold his desk for $5.00,

today's price would have been an estimated $118.00. His $3.50 profit he

could have made on his desk, would now be approximately $83.00. The price

of $8.25 he paid for his college textbooks, would now cost him almost

$200.00.

Looking at standard jobs and income in 1883 can give one an interesting

perspective on that era's economy. Job descriptions vary during this time

from an average farm laborer (New York) working an estimated 63 hours a

week and earning $1.25 a day to a glassblower/bottle maker (Massachusetts)

working an estimated 51 hours a week and earning $4.23 a day.4 Other

prices include men's apparel: a suit costing $4-$10, shoes $1-$3; women's

apparel: skirts costing $1.50-$2.50, shoes $.05-$1.50; entertainment

ranging from $1.50 opera tickets to $.15 museum tickets; food products:

$.04/lb. for sugar to $.10/lb. for roast beef. However, let us not forget

about Charles Alling's college tuition. Around the 1883 time period, he

would have paid approximately $200 a year for tuition.5 What would he say

about Hanover's $32,000 tuition today? Which in turn makes me wonder what

future Hanover students will say 150 years from now about our 2014 college

tuition fee.

As our glance into the economics and money value of 1883 comes to a

close, we can gain an appreciation and understanding of the quality of

life in early America. The value of a dollar is and will always be

determined directly through supply and demand, and these two contributing

factors are never stagnant. The ever-changing cycle will continue on

generation to generation. Just as my grandparents told me stories of their

cheap purchases in their younger years, so will I tell my future

grandchildren of mine: I remember the day when I only paid $3.30 for a

gallon of fuel.

Sources: Scott Derks, The Value of a Dollar: 1860-1999 (New

York: Grey House Publishing, Inc., 1999), xi, xix, 12; Kimberly Amadeo,

What Is the Value of a Dollar Today? About News, 17 Sept. 2014 http://useconomy.about.com/od/inflationfaq/f/value_of_a_dollar_today.htm

(assessed 27 Sept. 2014).

-- Clarissa Akers, HC 2015

Presumably, the church being referenced here was the old 2nd Presbyterian

Church located in Madison at 101 East Main Street. The church was

constructed in 1835, and the building remains, though the church no longer

resides there. Today it is named the 'John T. Windle Auditorium' and is

said to be open to the public for cultural and presentations and other

special events.

Source: Ron Grimes and Bob Thomas, Jefferson County

Historical Society volunteers, conversation with author, 22 Sep. 2010.

-- Brandon Doub, HC 2013

In the 21st century, the YMCA is typically referred to as a gym or place of

recreation with disregard to its religious affiliation in the previous

century. The YMCA was established in London in 1844 as an evangelical lay

organization (Zald, 216) with goals to help young men by the means religious

influence. This institution offered a number of services to paying members.

The YMCA also served as a place to encourage men to lead a better life,

which Charles Alling has brought to attention in his diary from 1883 from

his time at Hanover College. The YMCA originated at Hanover College on Sept.

24, 1870 (Whitney, 1) and was the first college to build a YMCA on its

campus. According to Alling's diary entry from September 17th 1883, the

building was an improvement to Hanover. It was revolutionary for Hanover, a

Presbyterian-affiliated campus, to have such an organization that would

encourage a more religious integrated campus. This addition to the campus

would have helped influence and motivate the students. After all, YMCA

stands for Young Men's Christian Association therefore it proves to fit at

Hanover College to motivate the attending young men.

During the late nineteenth century, the YMCA's primary focused was on

religious proselytization, (Zald, 216) that concentrated on Biblical

scripture. Included in this emphasis on spirituality, there would be a

minister employed at the YMCA who would give sermons, teach, and lead the

young men through various activities. As claimed by Alling, he attended an

influential meeting in the new YMCA hall that had quite an effect on me

and I have lived a better day than for many past. A sermon was a typical

spiritual activity offered to its members. Other activities that would

have been offered include prayer meetings and Bible readings. This

reaction by Alling reflects the success of the YMCA's methods to maintain

its motto to develop a well-rounded man.

At the turn of the century, the interest in religion decreased therefore,

the organization shifted to a focus emphasizing character development and

recreation. The YMCA offered more enhancement activities to help people

progress in their careers. The programs offered courses in typing, human

resources, and management, to name a few. The recreation activities helps

people to develop (Zald, 221), which included athletic activities that

ranged from dancing classes to card games. Overall the YMCA maintained its

goal to help advance members whether it was spiritually, physically or

mentally. As seen in the first account of Charles Alling, the culture of

the YMCA towards the end of the nineteenth century successfully influenced

Alling through the means of spirituality.

Sources: Pat Whitney, New Uses for Oldest College YMCA, Madison

Courier, 10 April 2010, madisoncourier.com

(accessed Sept 29, 2014); Mayer N. Zald and Patricia Denton, From

Evangelism to General Service: The Transformation of the YMCA, Administrative

Science Quarterly, Vol.8, No.2 (1963), 214-23.

-- Marissa Peppel, HC 2014

Hanover Historical Texts Project

Hanover College Department of History