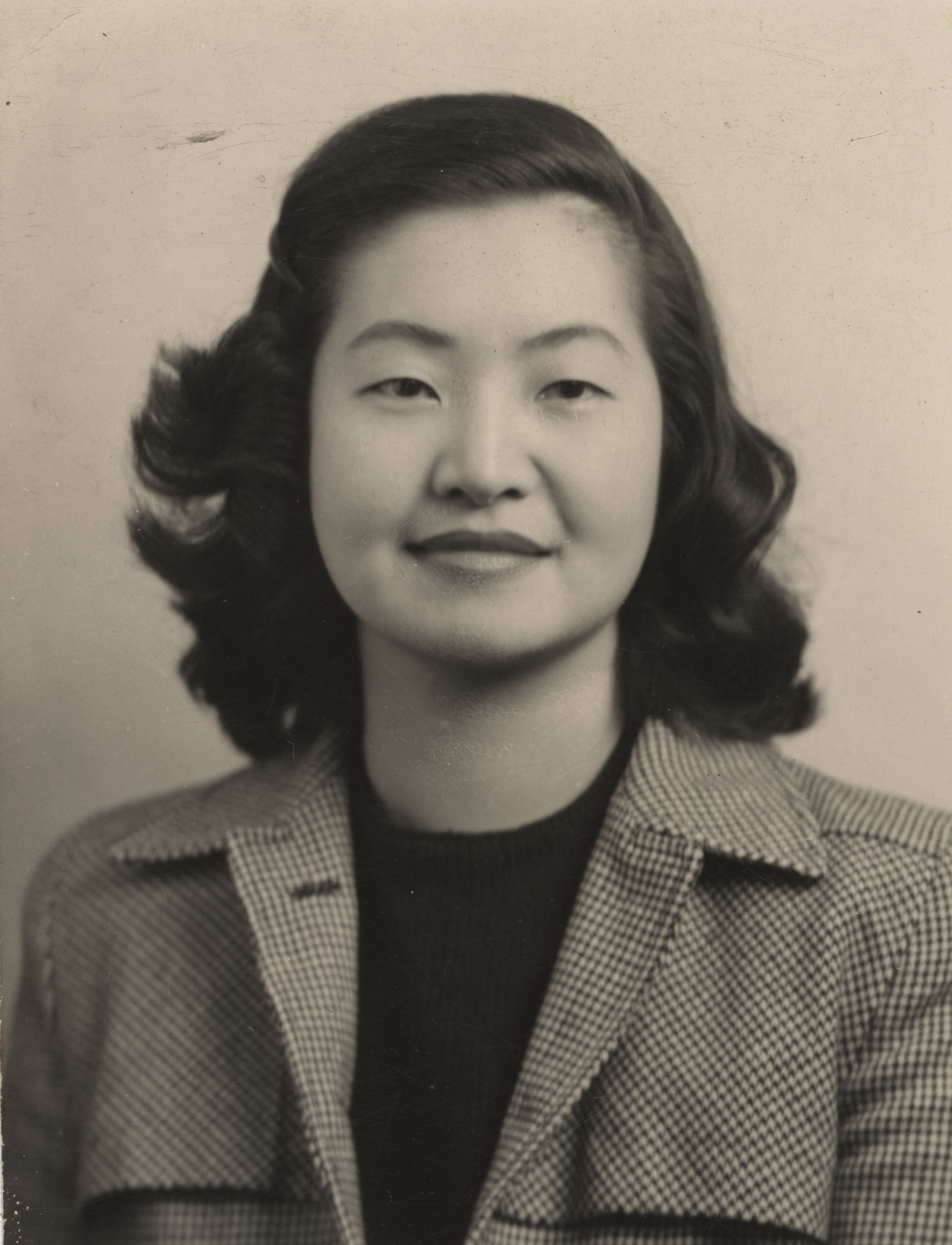

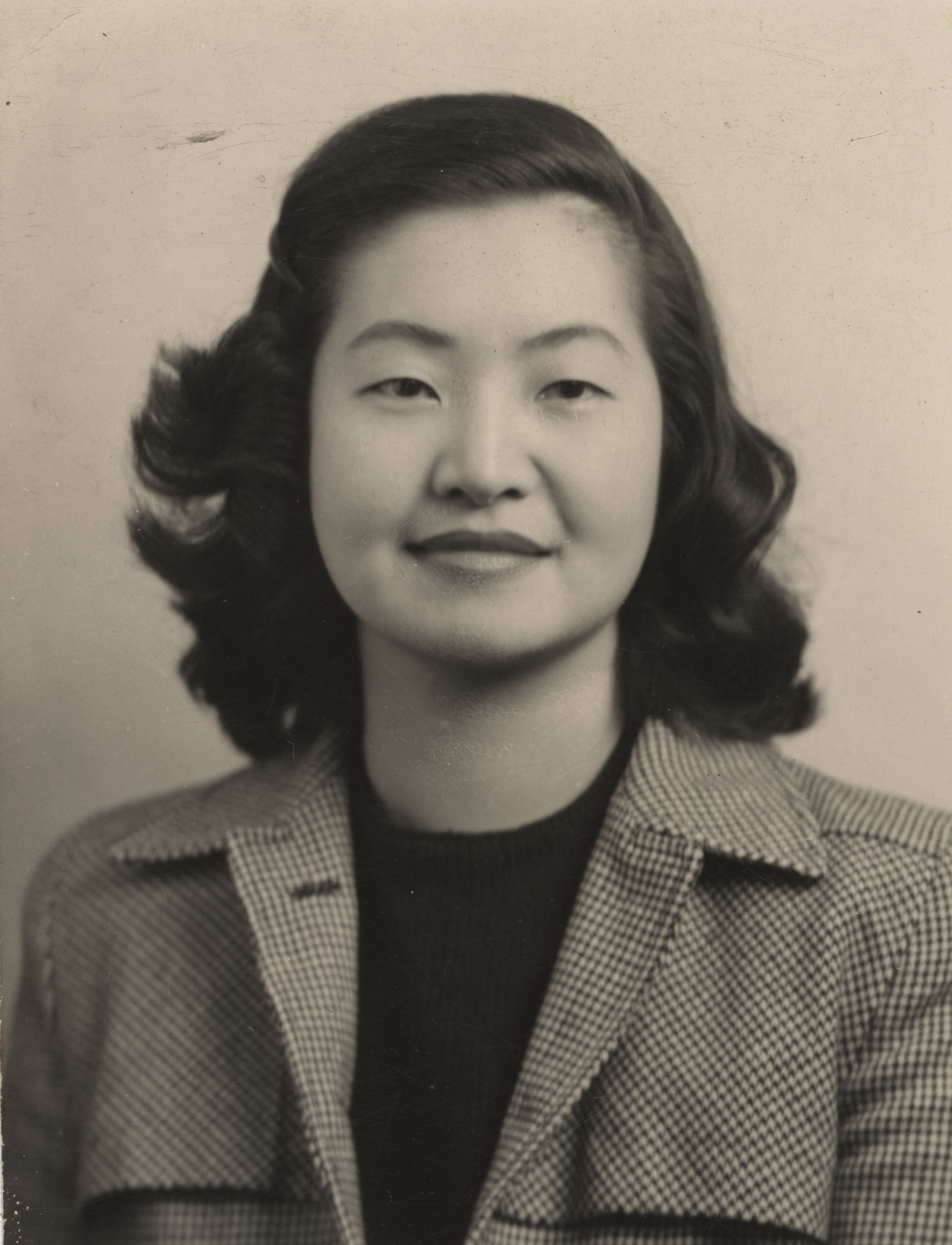

Monica

Itoi at Hanover College

Monica

Itoi at Hanover College

Excerpts from a print document in the archives of Hanover College, a Digital Text at newspapers.com, and another Digital Text at google books.

Monica Itoi enrolled at Hanover College in 1943, shortly after being released from internment in a relocation camp where her parents and neighbors continued to be held until war's end. In 1953, she published an autobiography (Nisei Daughter) using her married name, Monica Sone. Now in its third edition, her book is often assigned to college students for its descriptions of her childhood as a Japanese American in Seattle and of her experiences during the war. The book concludes with a chapter on Hanover (which she calls "Wendell College").

Note that Mrs. A. G. Parker and Anne Parker, mentioned below, were the wife and daughter of Hanover's president. "Nisei" refers to the American-born children of immigrants from Japan; "Nikkei" refers to all immigrants of Japanese descent.

(NB: Paragraph numbers apply to this excerpt, not the original source.)

"Four Nisei Girls Join Hanover Students," Triangle, 10 Sept. 1943, p. 1.

Hanover College is one of the many United States colleges in which Nisei, that is, second generation Japanese-Americans who have been born in this country, educated in American schools, and are loyal American citizens, have been placed as students with the help of the government. The four Nisei who will be members of the Hanover student body this year are Mitsuye Uyeta, Monica Itoi, Ayako Ota, and Michiko Hara. . . .

Monica Itoi will be a sophomore. She had her first year of college work at the University of Washington. . . . For the past summer, she has been working in a dentist's office in Indianapolis and has been living at the home of Rev. and Mrs. John B. Ferguson of the Irvington Presbyterian Church. She will room at Mrs. Berger's home, and eat at Donner Hall.

Ayako Ota and Michiko Hara will enter as Freshmen after graduating from the high school in the government Relocation Center at Topaz, Utah. The assistant principal of the school was at Hanover this summer as a leader of the Evangelical and Reformed Church Young People's Conference. Through him these girls heard of Hanover and decided to come here.

Monica

Itoi at Hanover College

Monica

Itoi at Hanover College

"Charlestown, Arch B. Taylor, Jr., Minister," Charlestown (Indiana) Courier, 28 Oct. 1943, p. 2.

Mitsuye Uyeta and Monica Itoi, Americans with Japanese faces; Mrs. A. Parker, Anne Parker and Dorothy Mueller, Moderator of the Youth of Synod, were guests of the young people at their regular meeting Sunday evening, and took part in a panel discussion; telling of personal experience in a relocation center. Young People from Otisco and Miller Chapel were present. A pitch-in dinner was enjoyed at six.

Monica Sone, 1979 preface to Nisei Daughter (1953; Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1979), xv-xvii.

Twenty-six years have passed since Nisei Daughter first came out in 1953. My narrative ended at a point where my brother, sister, and I left camp to go to our respective destinations. St. Louis, New Jersey, and Indiana. Our parents still remained in camp. They could not return to [our home in] Seattle since the West Coast was still off limits to the Japanese.

The ten concentration camps, which received 120,000 of us in 1942, were finally closed in 1946.

From Hanover College in southern Indiana, I went on to Western Reserve University to study clinical psychology. I married Geary Sone, a Nisei veteran from California. . . .

Today my mother, brother, Henry, and his wife, Minnie, live in Seattle. . . . Mother is now an American citizen, thanks to the efforts of the Japanese American Citizens League with Congress. It was too late for father, who died in 1949.

As a result of years of reflection by the Nikkeis about their unique experience as Americans of Japanese ancestry, certain ideas and feelings have become distilled and crystallized into a strong determination. The Nikkeis are moving out into the public eye, to attend to unfinished business with the government. Their primary goal is to have the government address the constitutional issue of the evacuation. There will also be a petition for redress from Congress.

In our bicentennial year of 1976, upon recommendation of the Japanese American Citizens League, President Gerald R. Ford rescinded Executive Order 9066. He acknowledged that the mass incarceration was a national mistake. This was a small, but significant step toward righting a wrong.

During Thanksgiving of 1978, the Japanese American Citizens League began its redress campaign by observing its first "Day of Remembrance" ceremony in Seattle. Similar public ceremonies followed in Portland, San Francisco, and Los Angeles.

So that their story will not be forgotten and lost to future generations, the Nikkeis are telling the nation about 1942, a time wen they became prisoners of their own government, without charges, without trials. This happened because the President and Congress yielded to the pressures of agricultural and other economic interest groups on the West Coast, which for fifty years had tried to be rid of the Nikkeis. Mass media assisted in molding public opinion to this end. Most astounding of all, the Supreme Court chose not to touch the issue of the Niseis' civil liberties as American citizens, selected solely on the basis of ancestry. The Court overlooked the vital American principle that consideration of guilt and punishment is to be carried out on an individual basis, and is not to be related to the wrongdoing of others. Justice Robert Jackson, in dissent, wrote, "The Supreme Court for all time has validated the principle of racial discrimination in criminal procedure."

The Nikkeis hope that this redress movement may discourage similar injustices to others. They aim to work together with white America, to carry out our mutual task which Professor V. Rostow of Yale delineated in his writing: "Until the wrong is acknowledged and made right, we shall have failed to meet the responsibility of a democratic society . . . the obligation of equal justice."