Frances Putnam Pogle published this

handbook for public speaking in multiple editions between 1898 and

1912. They generally included both instruction on public speaking

and texts that one could deliver at parties or similar occasions.

Excerpts from a Digitized

Text at the Internet Archive.

"Elocution"

In beginning the study with new pupils, the first thing I observe is

the manner in which they breathe.

Breathing

You should breathe deeply, or so that the lowest cells of the lungs can receive some fresh air with every inhalation. The expansion and contraction of the lungs should take place more in the lower, than in the upper parts. In fact, the chest should be used merely as a sounding board, or resonance cavity, through which the breath has to pass. This deep, even breathing is what gives the clear, ringing tones to the voice.

Without it, a voice will not carry. It is what enables orators to

speak for hours at a time without apparent effort. We find the deep

breathing more frequently in men than in women, probably because the

former wear looser clothing. . . .

Focusing the Tone

Another thing to be careful about, is the focusing of the tone. Unless you are particular about this your words will be muffled and "throaty." . . .

To focus your tone properly, take any word which begins with m, as more or man, and say it slowly, holding on to the m until the sound rings in the upper part of the head, and makes the lips tingle; in other words, think or focus the tone at the lips.

Many people waste breath by letting the tone come up in a slip shod manner, and strike the roof of the mouth, from which it has to rebound in order to reach the lips. When the tone rebounds, much of it goes down the throat again and muffles the next tone. Throw your tone like a ball, letting it make a curve at the back of the mouth and be free of obstacles until it reaches the lips.

You will be materially helped in focusing your tone, if you place your

lips in position to say the word, before you say it. . . .

Loudness

To acquire loudness of voice, there is nothing better than sustained

shouting.

[Exercise 1]

Imagine yourself on a storm-tossed boat, watching for a rescuing sail.

You see one, and, putting your hand to your mouth, you shout as loudly

and clearly as you can (for your life depends upon it.)

"Ship ahoy!"

(Repeat five times) . . .

Distinctness

Many people are very indistinct in their speech for the simple reason that they are slovenly in pronunciation. They are very apt to omit a letter or an entire syllable from a word, thereby making it indistinct; or perhaps they have a habit of letting the voice fall at the end of a word, thereby causing it to be inaudible.

Remember that it is just as important to pronounce the last letter or syllable distinctly, as the middle or first.

A good way to cure this is to practice, at first slowly and distinctly,

and then quickly and distinctly, difficult combinations of consonants in

words, and difficult combinations of words in sentences. . . .

Difficult Sentences:

1. Amos Ames, the amiable aeronaut, aided in an aerial enterprise at the

age of eighty-eight.

2. A big black bug bit a big black bear.

3. Bring a bit of buttered bran bread.

4. Geese cackle, cattle low, crows caw, cocks crow. . . .

Flexibility of the Voice

Often one will read along without ever lowering or raising the pitch of the voice. This produces a monotonous effect.

1. In order to cure this defect, practice on the vowels, first at the natural talking pitch, then a half-tone higher, and so on until you get to your highest limit. Then go back to the conversational pitch and lower the voice a half-tone at a time until you come to the lowest level. Work more on the high and low tones in this exercise as these are always the weakest.

2. Take any word, as, for instance yes, and pronounce it in

such ways that it will express surprise, positiveness, suspense, doubt,

unwillingness, eagerness, etc. . . .

Slowness

Never recite fast. . . . Though I have not put this caution near the first, yet, tome, it is one of the most important.

To begin with, when you get up to recite, always take time to place your audience, and give them time to become quiet, before you so much as open your lips. Then announce your subject and the author if you know by whom your selection was written . This always gives time to collect your thoughts and begin well, which is very important. If you begin well you hold your audience from the first, and do not have to work to gain their attention.

After announcing your subject and author, pause a second and then begin very slowly. Remember that the ideas you are presenting are comparatively new to your audience, and give them a second's time in which to recover from one volley, before you fire another point-blank at them. . . .

Remember that often a pause is more eloquent than words, and that nothing will emphasize a thought more strongly than to pause before or after it; or both before and after it. For instance, in Daniel Webster's "Supposed Speech of John Adams," what could be more effective than the pauses in the last sentence? "Independence now --- , and independence --- for ever. . . .

In closing, let me remark that all I have said heretofore, will count

as nothing, if you do not possess the key which unlocks all hearts, --

feeling !

Remarks by the Editor

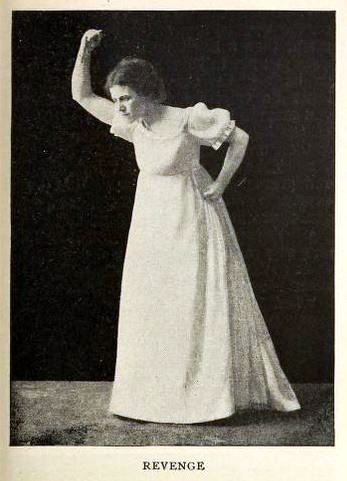

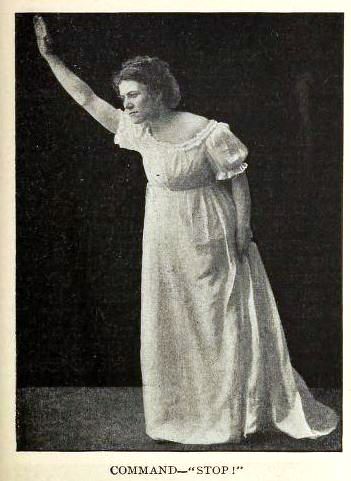

In common with the highest authorities on elocution and oratory, Miss Pogle believes and teaches that no two persons would express the same emotion by the same gesticulation, any more than they would do so in the same words. Therefore, the attitudes shown [in the following images] should be taken merely as suggestions for the expression of the sentiments or emotions indicated.

It is impossible to harness the expression of passion to a schedule.

And yet gesticulation can and should be cultivated by the proper training of the body and muscles, under the foregoing rules, to act in natural and graceful harmony with the mind. The arms and the body may be made to talk quite as naturally and oft times far more eloquently, than the voice.

The writer will never forget an instance of the power of gesticulating which came under his own observation. The distinguished lawyer and senator, Daniel W. Voorhees, was defending a man tried for murder in a Kentucky court. After giving the prosecuting witness an unmerciful flaying, he closed his address with the sentence: "His path lies downward." That may seem to the reader rather a feeble climax, but as the orator uttered these four words, with a deep thrilling tone that reverberated through the court room like a clarion note, he gradually raised his right arm, palm downward, from his hip to above the level of his head. His eyes were fixed upon the floor, and the feeling that he was staring into some profound, unmeasurable abyss was flashed like magic into the brain of every one present. The effect was tremendous. There was no particular reason why such a gesture should have expressed depth, but it did. It was the soul of the orator in the gesture; and, after all, that is the true genius of gesticulation.

Return to the History Department.