[Page 157]

EMPEDOKLES, son of Meton, grandson of an Empedokles who was a victor at Olympia, made his home and Akragas in Sicily. He was born about 494 B.C., and lived to the age of sixty. The only sure date in his life is his visit to Thourioi soon after its foundation (444). Various stories are told of his political activity, which may be genuine traditions; these illustrate a democratic tendency. At the same time he claimed almost the homage due to a god, and many miracles are attributed to him. His writings in some parts are said to imitate Orphic verses, and apparently his religious activity was in line with this sect. His death occurred away from Sicily—probably in the Peloponnesos.

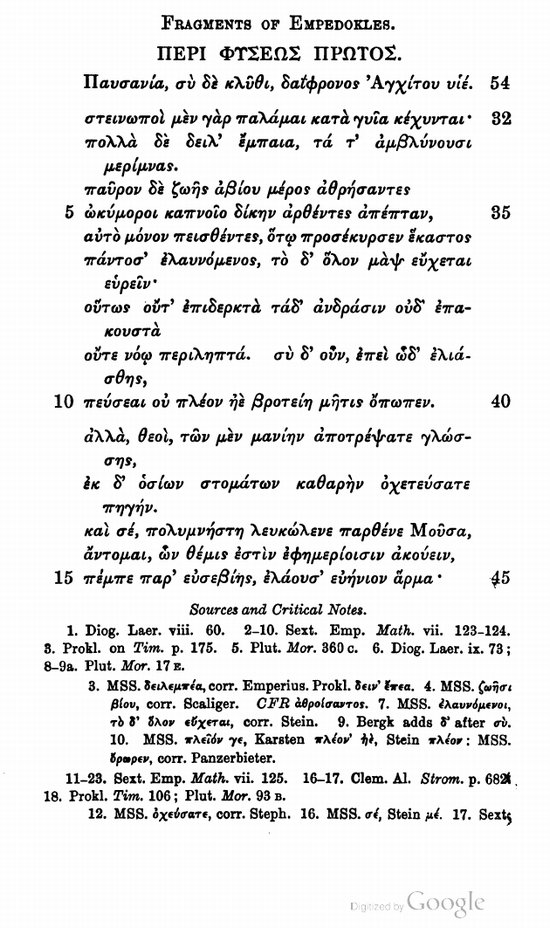

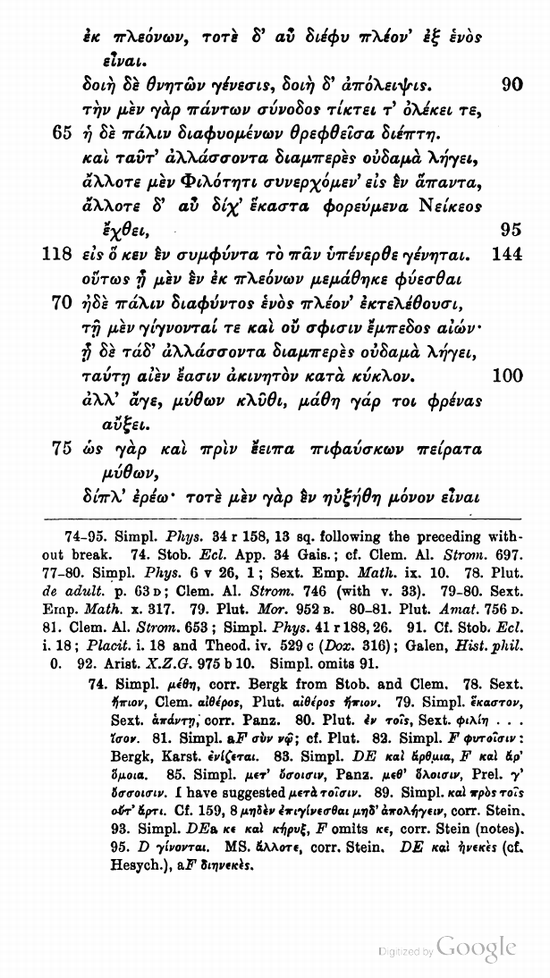

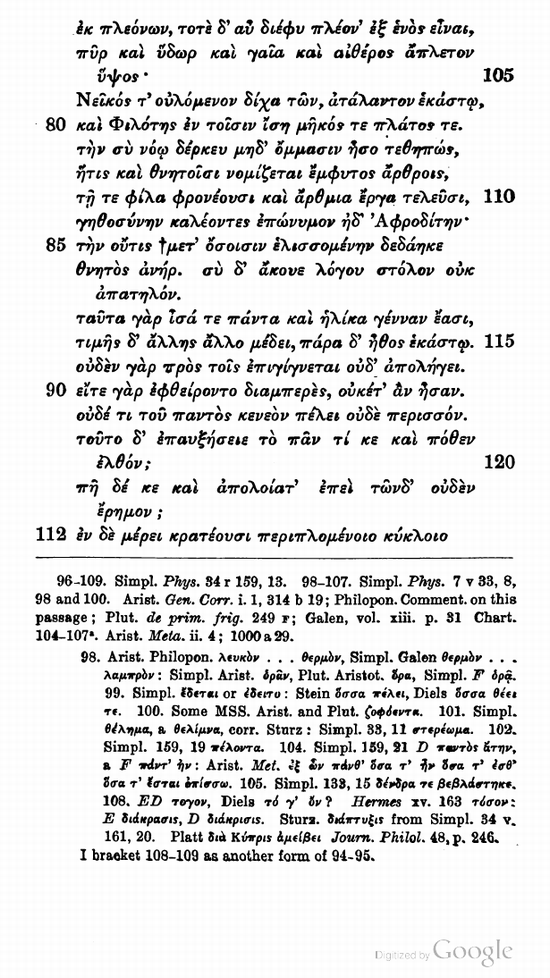

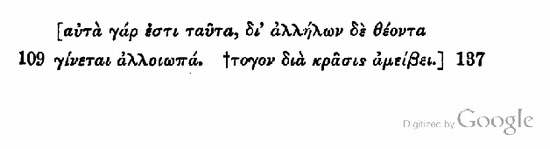

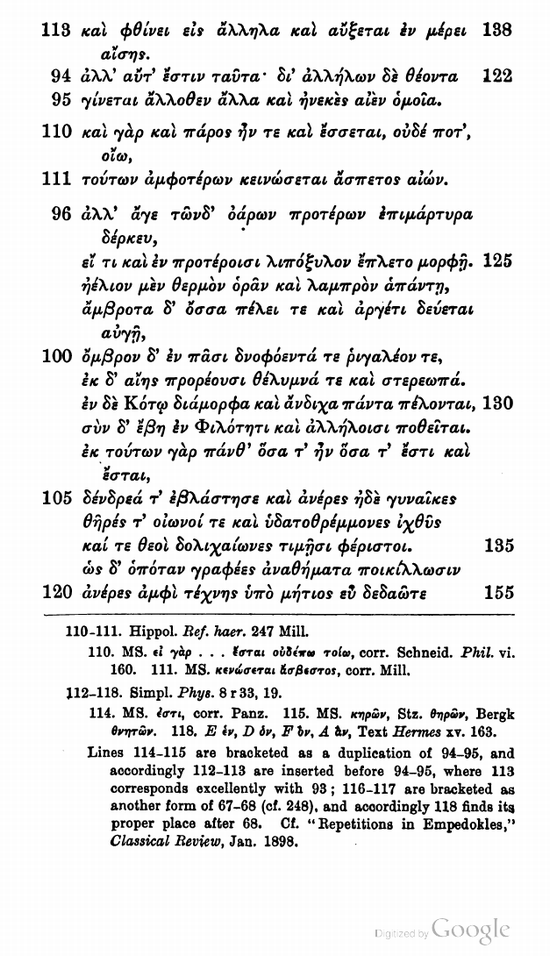

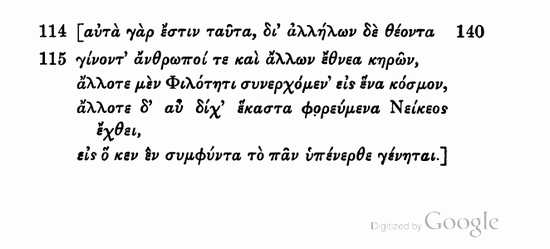

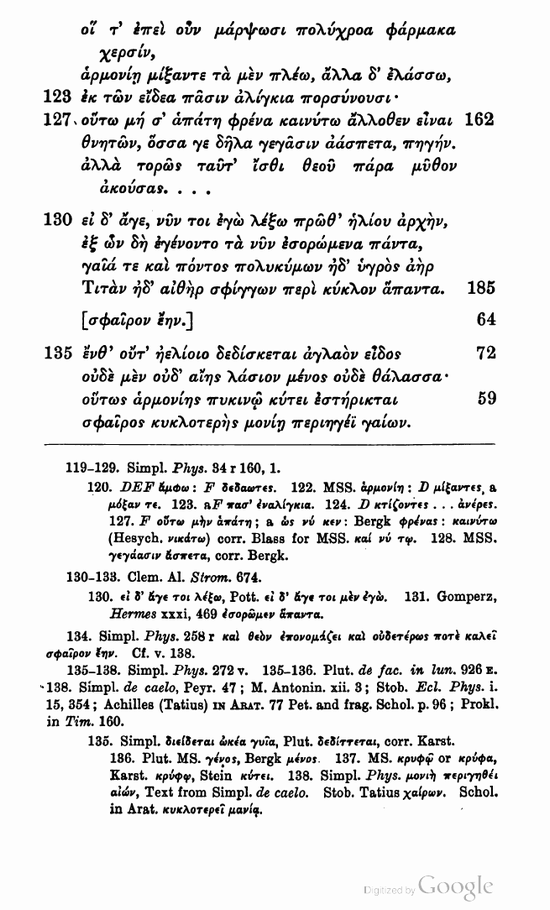

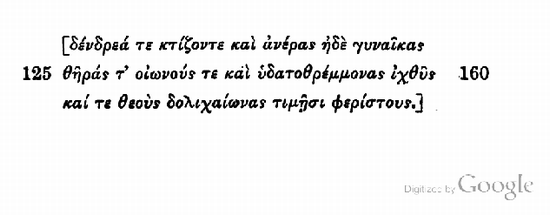

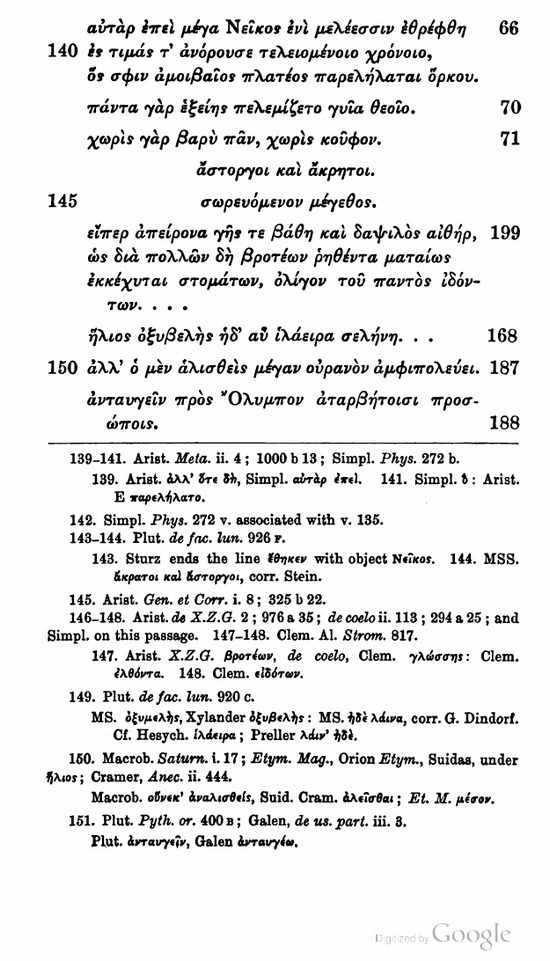

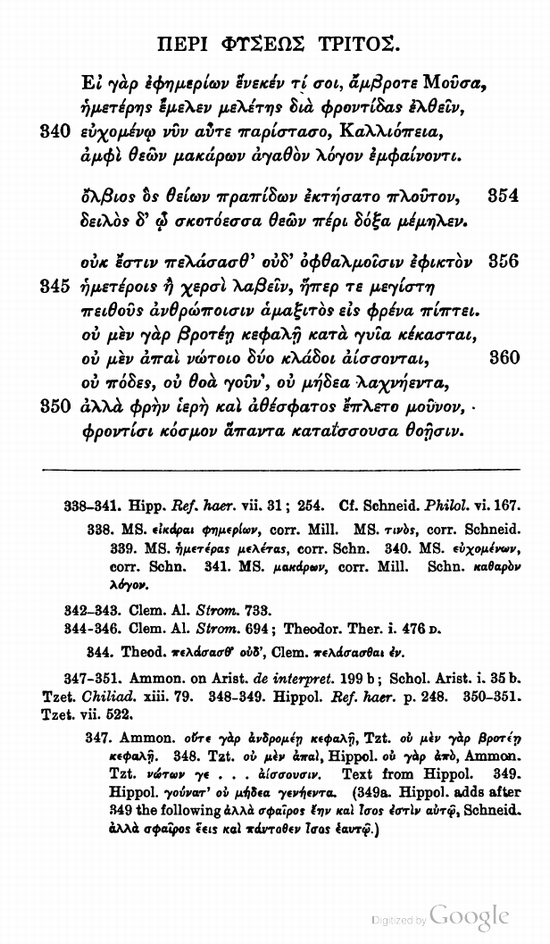

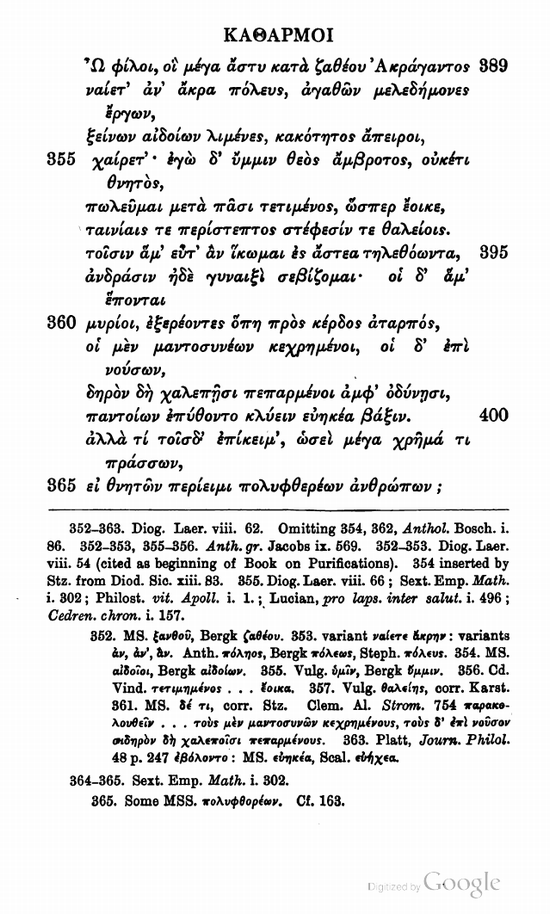

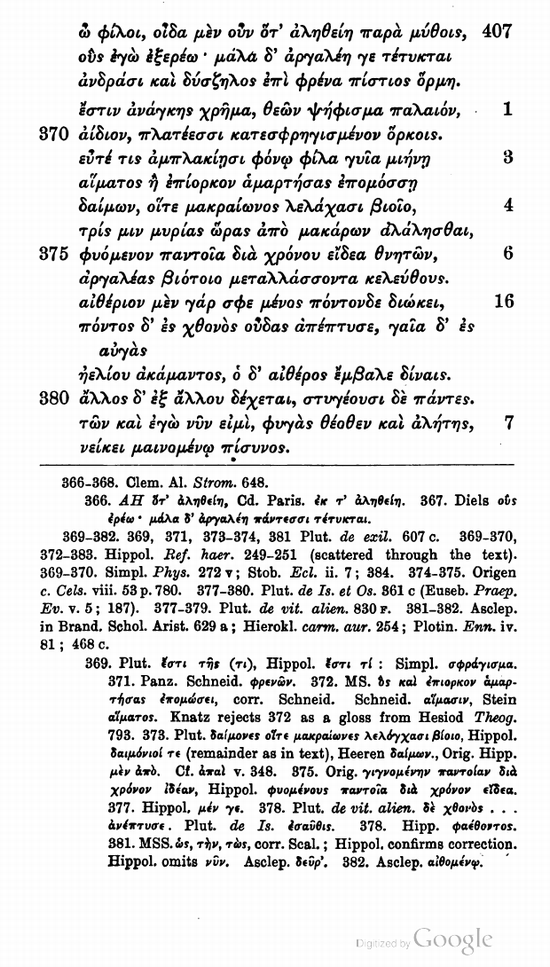

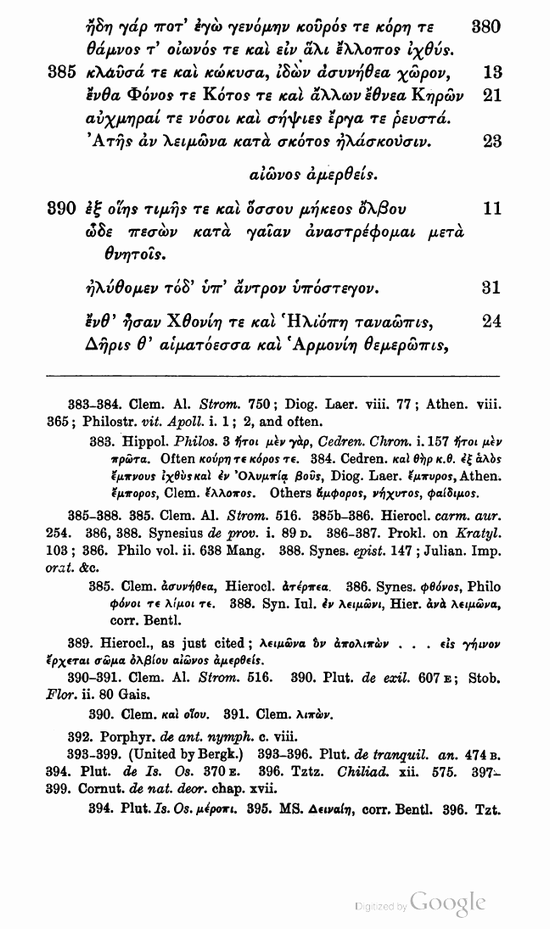

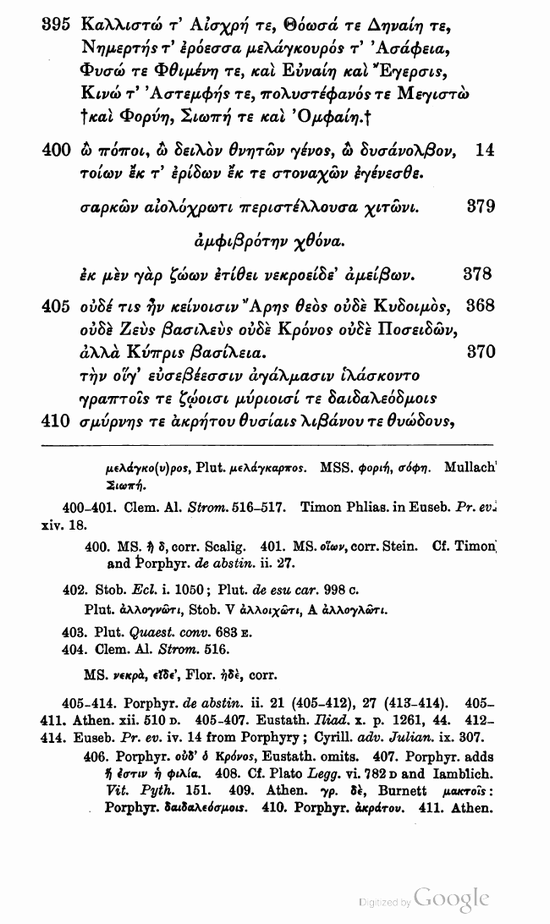

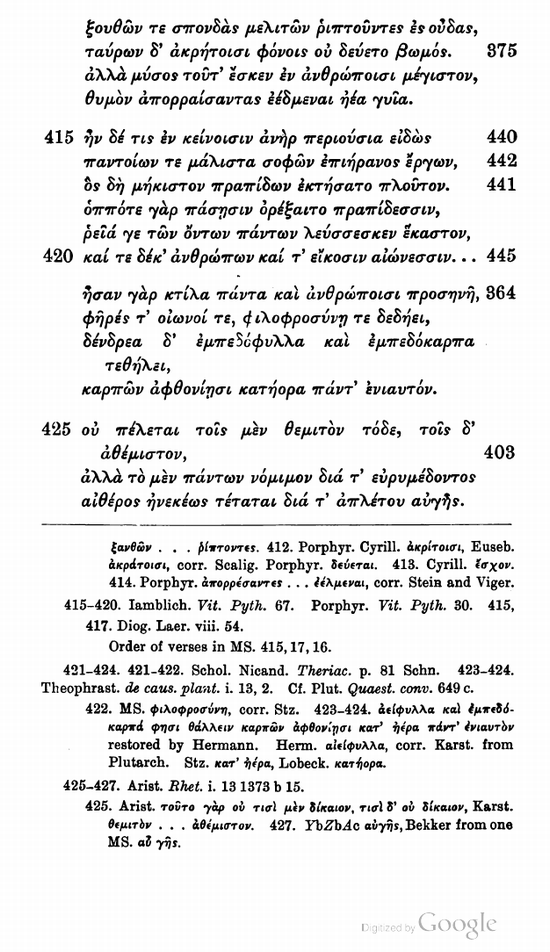

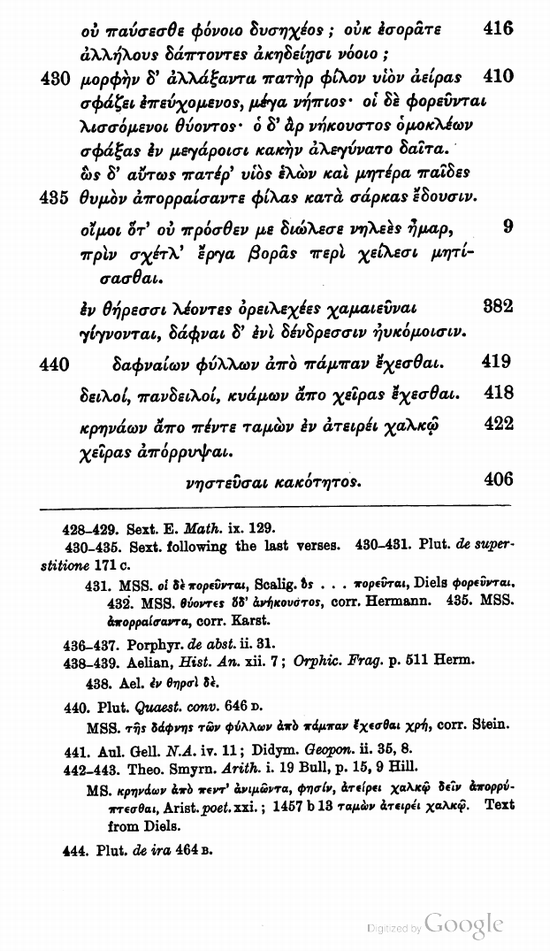

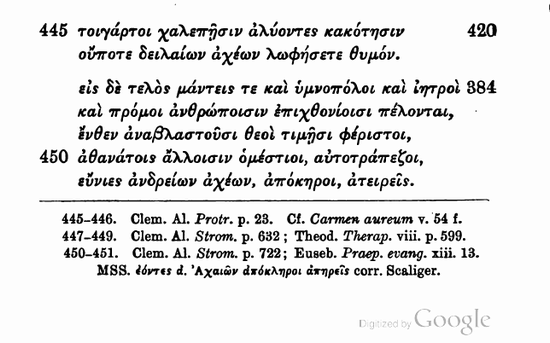

Note.—I print Stein's numbers at the left of the Greek text, Karsten's numbers at the right.

[Page 158]

[Page 159]

1. And do thou hear me, Pausanias, son of wise Anchites.

2. For scant means of acquiring knowledge are scattered among the members of the body; and many are the evils that break in to blunt the edge of studious thought. And gazing on a little portion of life that is not life, swift to meet their fate, they rise and are borne away like smoke, persuaded only of that on which each one chances as he is driven this way and that, but the whole he vainly boasts he has found. Thus these things are neither seen nor heard distinctly by men, nor comprehended by the mind. And thou, now that thou hast withdrawn hither, shalt learn no more than what mortal mind has seen.

11. But, ye gods, avert the madness of those men from my tongue, and from lips that are holy cause a pure stream to flow. And thee I pray, much-wooed white-armed maiden Muse, in what things it is right for beings of a day to hear, do thou, and Piety, driving obedient car, conduct me on. Nor yet shall the flowers of honour

[Page 160]

[Page 161]

well esteemed compel me to pluck them from mortal hands, on condition that I speak boldly more than is holy and only then sit on the heights of wisdom.

19. But come, examine by every means each thing how it is clear, neither putting greater faith in anything seen than in what is heard, nor in a thundering sound more than in the clear assertions of the tongue, nor keep from trusting any of the other members in which there lies means of knowledge, but know each thing in the way in which it is clear.

24. Cures for evils whatever there are, and protection against old age shalt thou learn, since for thee alone will I accomplish all these things. Thou shalt break the power of untiring gales which rising against the earth blow down the crops and destroy them; and, again, whenever thou wilt, thou shalt bring their blasts back; and thou shalt bring seasonable drought out of dark storm for men, and out of summer drought thou shalt bring streams pouring down from heaven to nurture the trees; and thou shalt lead out of Hades the spirit of a man that is dead.

33. Hear first the four roots of all things: bright Zeus, life-giving Hera (air), and Aidoneus (earth), and Nestis who moistens the springs of men with her tears.1

1. Cf. Dox. p. 99, n. 3.

[Page 162]

[Page 163]

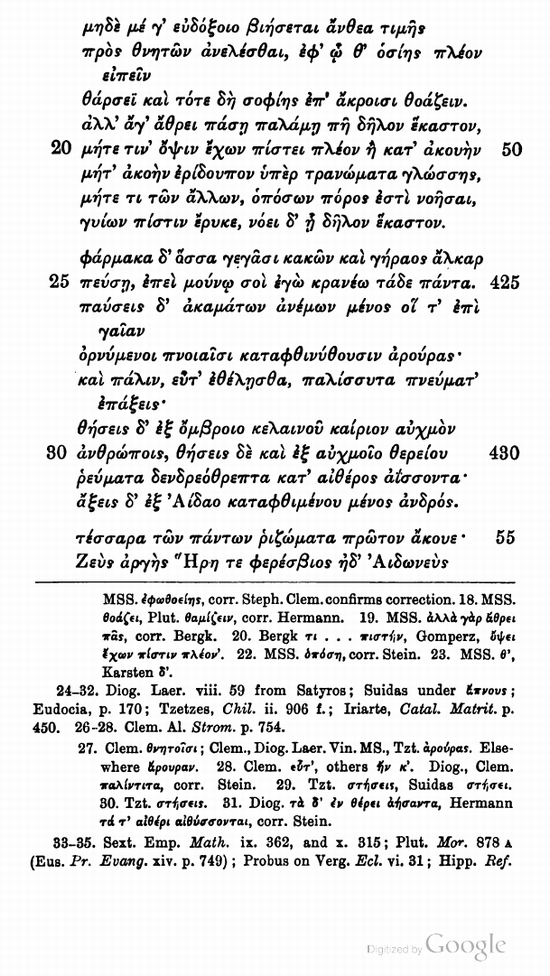

36. And a second thing I will tell thee: There is no origination of anything that is mortal, nor yet any end in baneful death; but only mixture and separation of what is mixed, but men call this 'origination.'

40. But when light is mingled with air in human form, or in form like the race of wild beasts or of plants or of birds, then men say that these things have come into being; and when they are separated, they call them evil fate; this is the established practice, and I myself also call it so in accordance with the custom.

45. Fools! for they have no far-reaching studious thoughts who think that what was not before comes into being or that anything dies and perishes utterly.

48. For from what does not exist at all it is impossible that anything come into being, and it is neither possible nor perceivable that being should perish completely; for things will always stand wherever one in each case shall put them.

[Page 164]

[Page 165]

51. A man of wise mind could not divine such things as these, that so long as men live what indeed they call life, so long they exist and share what is evil and what is excellent, but before they are formed and after they are dissolved, they are really nothing at all.

55. But for base men it is indeed possible to withhold belief from strong proofs; but do thou learn as the pledges of our Muse bid thee, and lay open her word to the very core.

58. Joining one heading to another in discussion, not completing one path (of discourse) . . . for it is right to say what is excellent twice and even thrice.

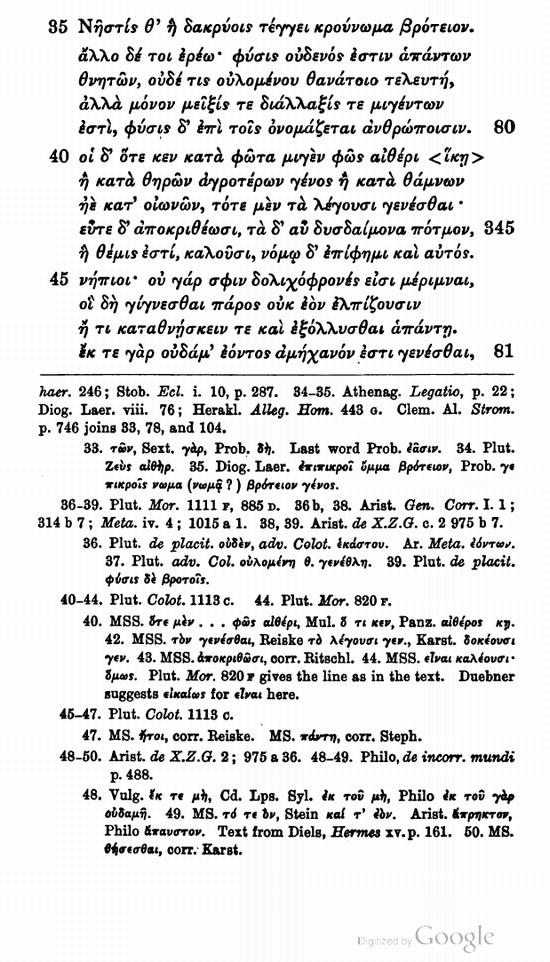

60. Twofold is the truth I shall speak; for at one time there grew to be one alone out of many, and at another time, however, it separated so that there were many out of the one. Twofold is the coming into being, twofold the passing away, of perishable things; for the latter (i.e. passing away) the combining of

[Page 166]

[Page 167]

all things both begets and destroys, and the former (i.e. coming into being), which was nurtured again out of parts that were being separated, is itself scattered.

66. And these (elements) never cease changing place continually, now being all united by Love into one, now each borne apart by the hatred engendered of Strife, until they are brought together in the unity of the all, and become subject to it. Thus inasmuch as one has been wont to arise out of many and again with the separation of the one the many arise, so things are continually coming into being and there is no fixed age for them; and farther inasmuch as they [the elements] never cease changing place continually, so they always exist within an immovable circle.

74. But come, hear my words, for truly learning causes the mind to grow. For as I said before in declaring the ends of my words: Twofold is the truth I shall speak; for at one time there grew to be the one

[Page 168]

[Page 169]

alone out of many, and at another time it separated so that there were many out of the one; fire and water and earth and boundless height of air, and baneful Strife apart from these, balancing each of them, and Love among them, their equal in length and breadth. 81. Upon her do thou gaze with thy mind, nor yet sit dazed in thine eyes; for she is wont to be implanted in men's members, and through her they have thoughts of love and accomplish deeds of union, and call her by the names of Delight, and Aphrodite; no mortal man has discerned her with them (the elements) as she moves on her way. But do thou listen to the undeceiving course of my words.1 . . .

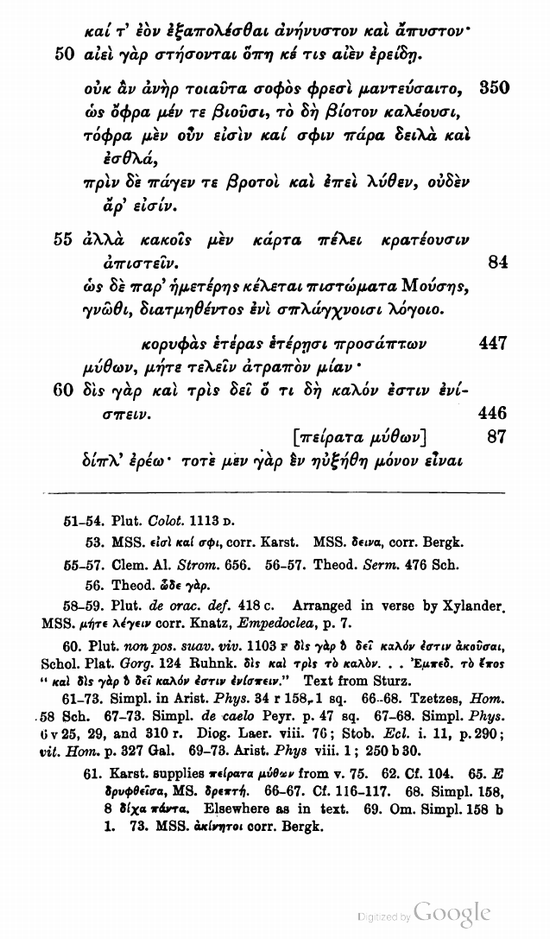

87. For these (elements) are equal, all of them, and of like ancient race; and one holds one office, another another, and each has his own nature. . . . For nothing is added to them, nor yet does anything pass away from them; for if they were continually perishing they would no longer exist. . . . Neither is any part of this all empty, nor over full. For how should anything cause this all to increase, and whence should it come? And whither should they (the elements) perish, since no place is empty of them? And in their turn they prevail as the cycle comes round, and they disappear before

1. Cf. Parmenides v. 112

[Page 170]

[Page 171]

each other, and they increase each in its allotted turn. But these (elements) are the same; and penetrating through each other they become one thing in one place and another in another, while ever they remain alike (i.e. the same).

110. For they two (Love and Strife) were before and shall be, nor yet, I think, will there ever be an unutterably long time without them both.

96. But come, gaze on the things that bear farther witness to my former words, if in what was said before there be anything defective in form. Behold the sun, warm and bright on all sides, and whatever is immortal and is bathed in its bright ray, and behold the raincloud, dark and cold on all sides; from the earth there proceed the foundations of things and solid bodies. In Strife all things are, endued with form and separate from each other, but they come together in Love and are desired by each other. 104. For from these (elements) come all things that are or have been or shall be; from these there grew up trees and men and women, wild beasts and birds and water-nourished fishes, and the very gods, long-lived, highest in honour.

121. And as when painters are preparing elaborate votive offerings—men well taught by wisdom in their

[Page 172]

[Page 173]

art—they take many-coloured pigments to work with, and blend together harmoniously more of one and less of another till they produce likenesses of all things; so let not error overcome thy mind to make thee think there is any other source of mortal things that have likewise come into distinct existence in unspeakable numbers; but know these (elements), for thou didst hear from a god the account of them.

130. But come, I will tell thee now the first principle of the sun, even the sources of all things now visible, earth and billowy sea and damp mist and Titan aether (i.e. air) binding all things in its embrace.

135. Then neither is the bright orb of the sun greeted, nor yet either the shaggy might of earth or sea; thus, then, in the firm vessel of harmony is fixed God, a sphere, round, rejoicing in complete solitude.

[Page 174]

[Page 175]

139. But when mighty Strife was nurtured in its members and leaped up to honour at the completion of the time, which has been driven on by them both in turn under a mighty oath. . . . .

142. For the limbs of the god were made to tremble, all of them in turn.

143. For all the heavy (he put) by itself, the light by itself.

144. Without affection and not mixed together.

145. Heaped together in greatness.

146. If there were no limit to the depths of the earth and the abundant air, as is poured out in foolish words from the mouths of many mortals who see but little of the all.

149. Swift-darting sun and kindly moon.

150. But gathered together it advances around the great heavens.

151. It shines back to Olympos with untroubled face.

[Page 176]

[Page 177]

152. The kindly light has a brief period of shining.

153. As sunlight striking the broad circle of the moon.

154. A borrowed light, circular in form, it revolves about the earth, as if following the track of a chariot.

156. For she beholds opposite to her the sacred circle of her lord.

157. And she scatters his rays into the sky above, and spreads darkness over as much of the earth as the breadth of the gleaming-eyed moon.

160. And night the earth makes by coming in front of the lights.

161. Of night, solitary, blind-eyed.

162. And many fires burn beneath the earth.

[Page 178]

[Page 179]

163. (The sea) with its stupid race of fertile fishes.

164. Salt is made solid when struck by the rays of the sun.

165. The sea is the sweat of the earth.

166. But air1 sinks down beneath the earth with its long roots . . . . For thus it happened to be running at that time, but oftentimes otherwise.

168. (Fire darting) swiftly upwards.

169. But now I shall go back over the course of my verses, which I set out in order before, drawing my present discourse from that discourse. When Strife reached the lowest depth of the eddy and Love comes to be in the midst of the whirl, then all these things come together at this point so as to be one alone, yet not immediately, but joining together at their pleasure, one from one place, another from another. And as they were joining together Strife departed to the utmost boundary. But many things remained unmixed, alternating

1. In Empedokles' verses, αἰθὴρ regularly means air.

[Page 180]

[Page 181]

with those that were mixed, even as many as Strife, remaining aloft, still retained; for not yet had it entirely departed to the utmost boundaries of the circle, but some of its members were remaining within, and others had gone outside. 180. But, just as far as it is constantly rushing forth, just so far there ever kept coming in a gentle immortal stream of perfect Love; and all at once what before I learned were immortal were coming into being as mortal things,1 what before were unmixed as mixed, changing their courses. And as they (the elements) were mingled together there flowed forth the myriad species of mortal things, patterned in every sort of form, a wonder to behold.

186. For all things are united, themselves with parts of themselves—the beaming sun and earth and sky and sea—whatever things are friendly but have separated in mortal things. And so, in the same way, whatever things are the more adapted for mixing, these are loved by each other and made alike by Aphrodite. But whatever things are hostile are separated as far as possible from each other, both in their origin and in their mixing and in the forms impressed on them, absolutely unwonted to unite and very baneful, at the suggestion of Strife, since it has wrought their birth.

1. θνητά, 'perishable things' in contrast with the elements, might almost be rendered as 'things on the earth.'

[Page 182]

[Page 183]

195. In this way, by the good favour of Tyche, all things have power of thought.

196. And in so far as what was least dense came together as they fell.

197. For water is increased by water, primeval fire by fire, and earth causes its own substance to increase, and air, air.

199. And the kindly earth in its broad hollows received two out of the eight parts of bright Nestis, and four of Hephaistos, and they became white bones, fitted together marvellously by the glues of Harmony.

203. And the earth met with these in almost equal amounts, with Hephaistos and Ombros and bright-shining Aether (i.e. air), being anchored in the perfect harbours of Kypris; either a little more earth, or a little less with more of the others. From these arose blood and various kinds of flesh.

208. . . . glueing barley-meal together with water.

209. (Water) tenacious Love.

[Page 184]

[Page 185]

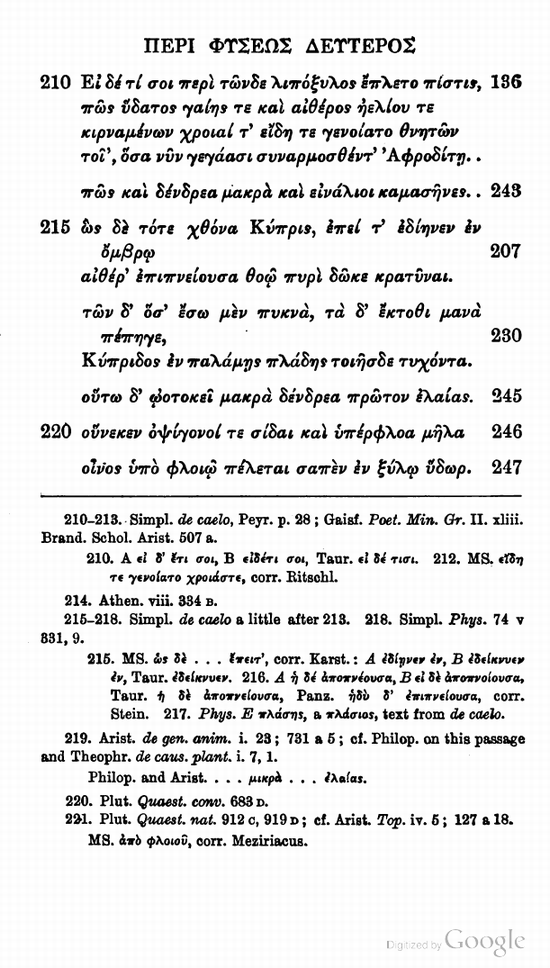

210. And if your faith be at all lacking in regard to these (elements), how from water and earth and air and sun (fire) when they are mixed, arose such colours and forms of mortal things, as many as now have arisen under the uniting power of Aphrodite. . . .

214. How both tall trees and fishes of the sea (arose).

215. And thus then Kypris, when she had moistened the earth with water, breathed air on it and gave it to swift fire to be hardened.

217. And all these things which were within were made dense, while those without were made rare, meeting with such moisture in the hands of Kypris.

219. And thus tall trees bear fruit (lit. eggs), first of all olives.

220. Wherefore late-born pomegranates and luxuriant apples . . .

221. Wine is water that has fermented in the wood beneath the bark.

[Page 186]

[Page 187]

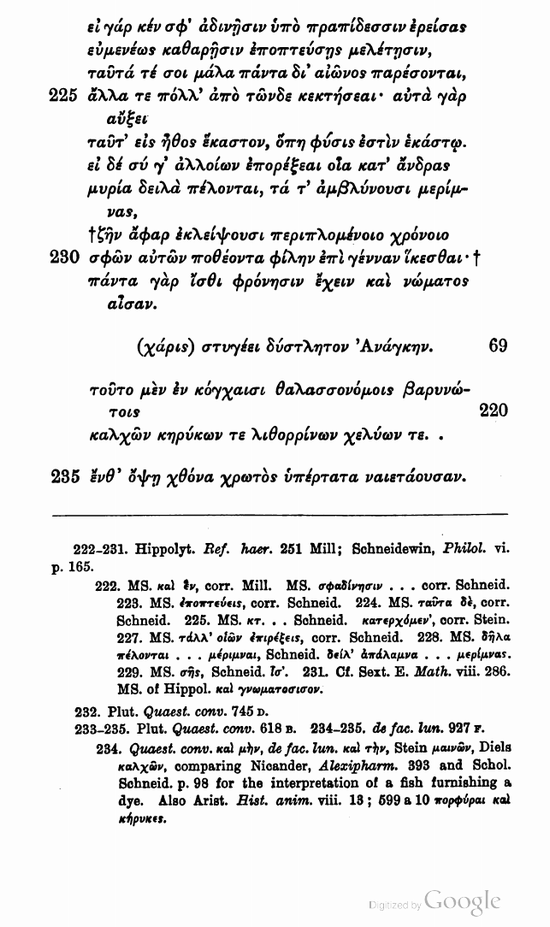

222. For if thou shalt fix them in all thy close-knit mind and watch over them graciously with pure attention, all these things shall surely be thine for ever, and many others shalt thou possess from them. For these themselves shall cause each to grow into its own character, whatever is the nature1 of each. But if thou shalt reach out for things of another sort, as is the manner of men, there exist countless evils to blunt your studious thoughts; †soon these latter shall cease to live as time goes on, desiring as they do to arrive at the longed-for generation of themselves.† For know that all things have understanding and their share of intelligence.

232. Favor hates Necessity, hard to endure.

233. This is in the heavy-backed shells found in the sea, of limpets and purple-fish and stone-covered tortoises . . . . there shalt thou see earth lying uppermost on the surface.

1. φυσις here seems to mean 'nature,' and not 'origin.'

[Page 188]

[Page 189]

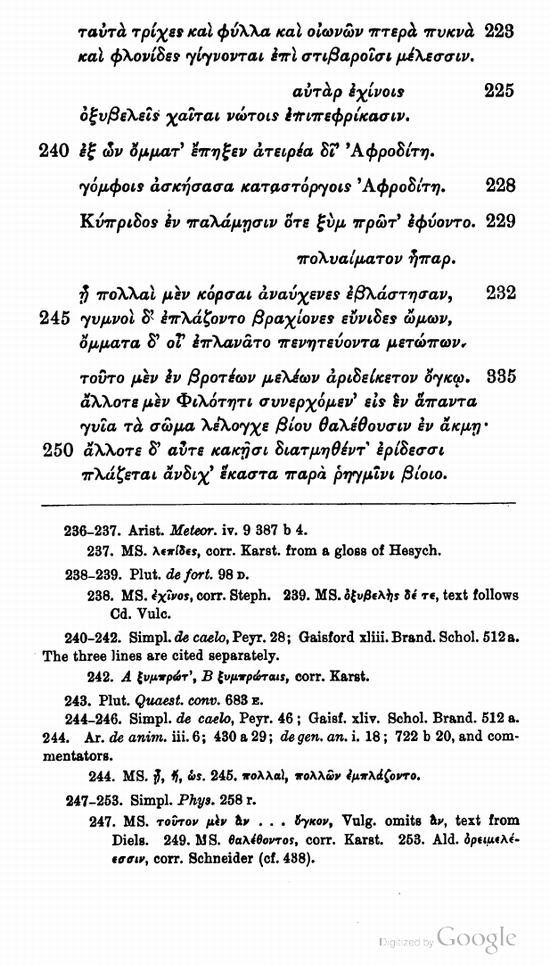

236. Hair and leaves and thick feathers of birds are the same thing in origin, and reptiles' scales, too, on strong limbs.

238. But on hedgehogs, sharp-pointed hair bristles on their backs.

240. Out of which divine Aphrodite wrought eyes untiring.

241. Aphrodite fashioning them curiously with bonds of love.

242. When they first grew together in the hands of Aphrodite.

243. The liver well supplied with blood.

244. Where many heads grew up without necks, and arms were wandering about naked, bereft of shoulders, and eyes roamed about alone with no foreheads.

247. This is indeed remarkable in the mass of human members; at one time all the limbs which form the body, united into one by Love, grow vigorously in the prime of life; but yet at another time, separated by evil Strife, they wander each in different directions along the breakers of the sea of life. Just so it is with

[Page 190]

[Page 191]

plants1 and with fishes dwelling in watery halls, and beasts whose lair is in the mountains, and birds borne on wings.

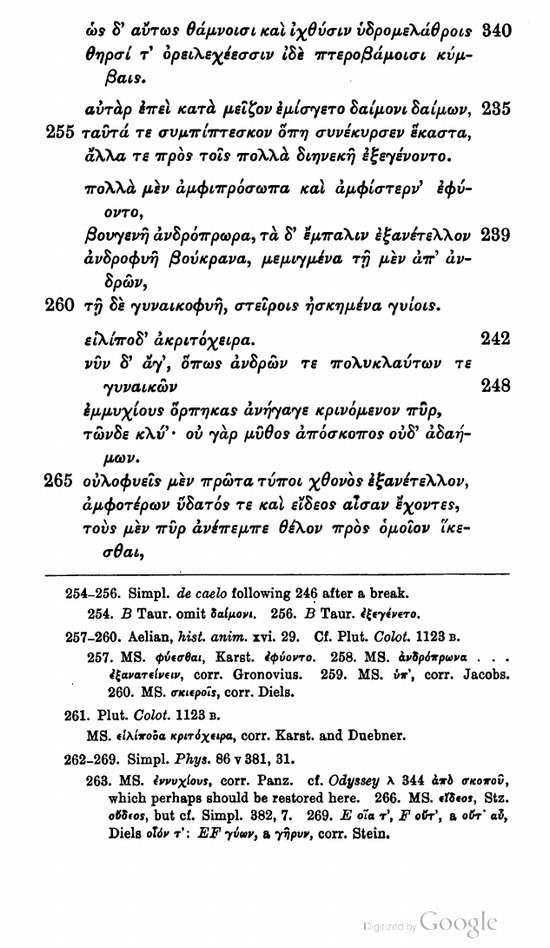

254. But as divinity was mingled yet more with divinity, these things kept coming together in whatever way each might chance, and many others also in addition to these continually came into being.

257. Many creatures arose with double faces and double breasts, offspring of oxen with human faces, and again there sprang up children of men with oxen's heads; creatures, too, in which were mixed some parts from men and some of the nature of women, furnished with sterile members.

261. Cattle of trailing gait, with undivided hoofs.

262. But come now, hear of these things; how fire separating caused the hidden offspring of men and weeping women to arise, for it is no tale apart from our subject, or witless. In the first place there sprang up out of the earth forms grown into one whole,2 having a share of both, of water and of fire. These in truth fire caused to grow up, desiring to reach its like; but they

1. θάμνος, 'bush,' I have rendered regularly as 'plant.'

2. Cf. Aet. v. 19; Dox. 430.

[Page 192]

[Page 193]

showed as yet no lovely body formed out of the members, nor voice nor limb such as is natural to men.

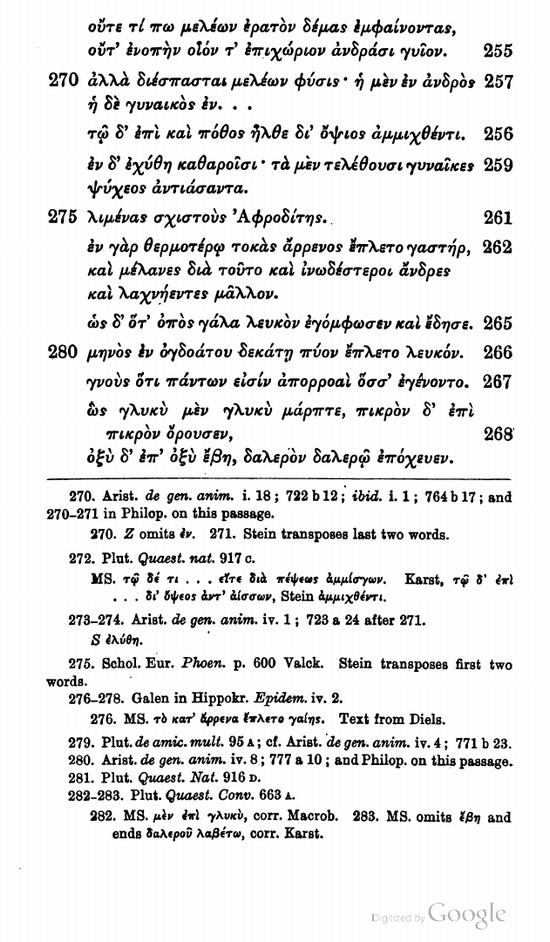

270. But the nature of the members (of the child?) is divided, part in the man's, part in the woman's (body).

271. But desire also came upon him, having been united with . . . by sight.

273. It was poured out in the pure parts, and some meeting with cold became females.

275. The separated harbours of Aphrodite.

276. In its warmer parts the womb is productive of the male, and on this account men are dark and more muscular and more hairy.

279. As when fig-juice curdles and binds white milk.

280. On the tenth day of the eighth month came the white discharge.

281. Knowing that there are exhalations from all things which came into existence.

281. Thus sweet was snatching sweet, and bitter darted to bitter, and sharp went to sharp, and hot coupled with hot.

[Page 194]

[Page 195]

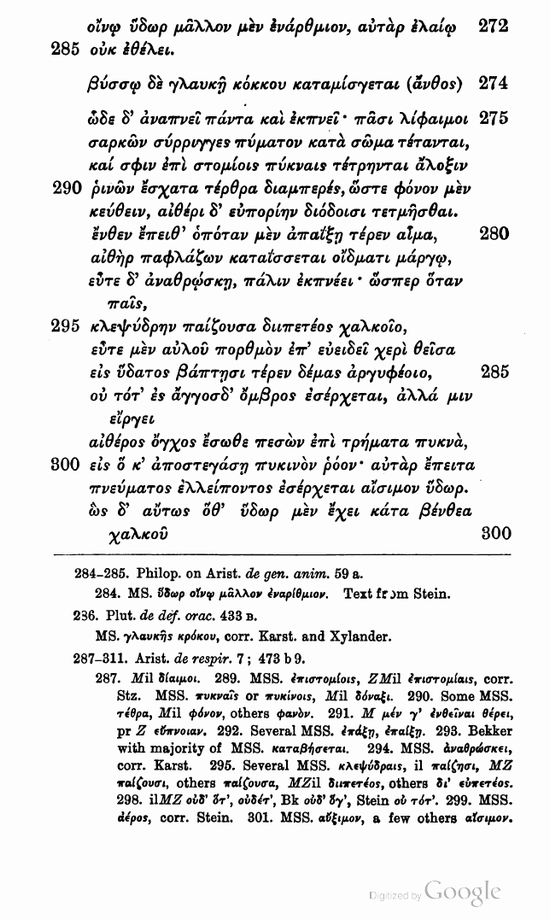

284. Water combines better with wine, but it is unwilling to combine with oil.

286. The bloom of the scarlet dye mingles with shining linen.

287. So all beings breathe in and out; all have bloodless tubes of flesh spread over the outside of the body, and at the openings of these the outer layers of skin are pierced all over with close-set ducts, so that the blood remains within, while a facile opening is cut for the air to pass through. Then whenever the soft blood speeds away from these, the air speeds bubbling in with impetuous wave, and whenever the blood leaps back the air is breathed out; as when a girl, playing with a klepsydra of shining brass, takes in her fair hand the narrow opening of the tube and dips it in the soft mass of silvery water, the water does not at once flow into the vessel, but the body of air within pressing on the close-set holes checks it till she uncovers the compressed stream; but then when the air gives way the determined amount of water enters. (302.) And so in the same way when the water occupies the depths of the bronze vessel, as long as the narrow opening and passage is blocked up by human flesh, the air outside striving eagerly to enter holds back the water inside behind the gates of the resounding tube, keeping control of its end, until she lets go with her hand.

[Page 196]

[Page 197]

(306.) Then, on the other hand, the very opposite takes place to what happened before; the determined amount of water runs off as the air enters. Thus in the same way when the soft blood, surging violently through the members, rushes back into the interior, a swift stream of air comes in with hurrying wave, and whenever it (the blood) leaps back, the air is breathed out again in equal quantity.

313. With its nostrils seeking out the fragments of animals' limbs, <as many as the delicate exhaltation from their feet was leaving behind in the wood.>

314. So, then, all things have obtained their share of breathing and of smelling.

315. (The ear) an offshoot of flesh.

316. And as when one with a journey through a stormy night in prospect provides himself with a lamp and lights it at the bright-shining fire—with lanterns that drive back every sort of wind, for they scatter the breath of the winds as they blow—and the light darting out, inasmuch as it is finer (than the winds), shines across the threshold with untiring rays; so then elemental fire, shut up in membranes, it entraps in fine coverings to be the round pupil, and the coverings protect it against the deep water which flows about it, but the fire darting forth, inasmuch as it is finer. . . .

[Page 198]

[Page 199]

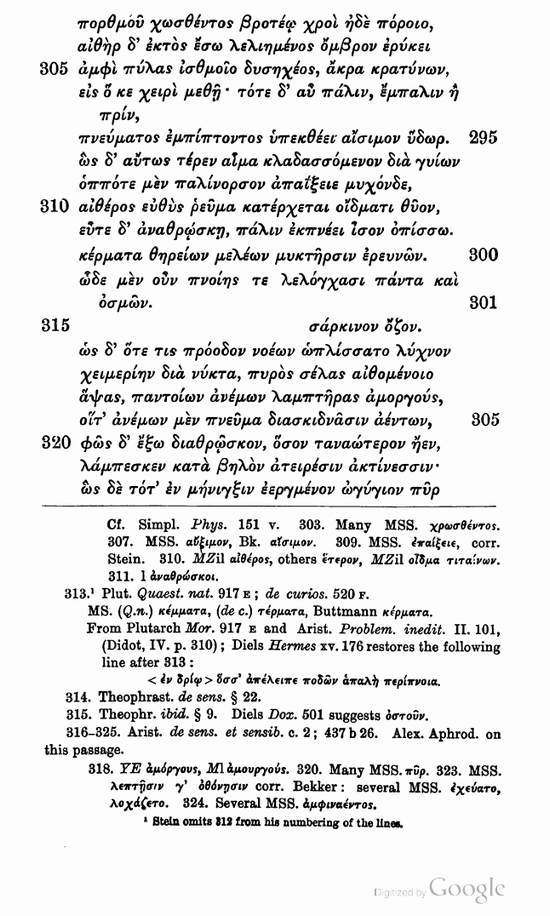

326. There is one vision coming from both (eyes).

327. (The heart) lies in seas of blood which darts in opposite directions, and there most of all intelligence centres for men; for blood about the heart is intelligence in the case of men.

330. For men's wisdom increases with reference to what lies before them.

331. In so far as they change and become different, to this extent other sorts of things are ever present for them to think about.

333. For it is by earth that we see earth, and by water water, and by air glorious air; so, too, by fire we see destroying fire, and love by love, and strife by baneful strife. For out of these (elements) all things are fitted together and their form is fixed, and by these men think and feel both pleasure and pain.

[Page 200]

[Page 201]

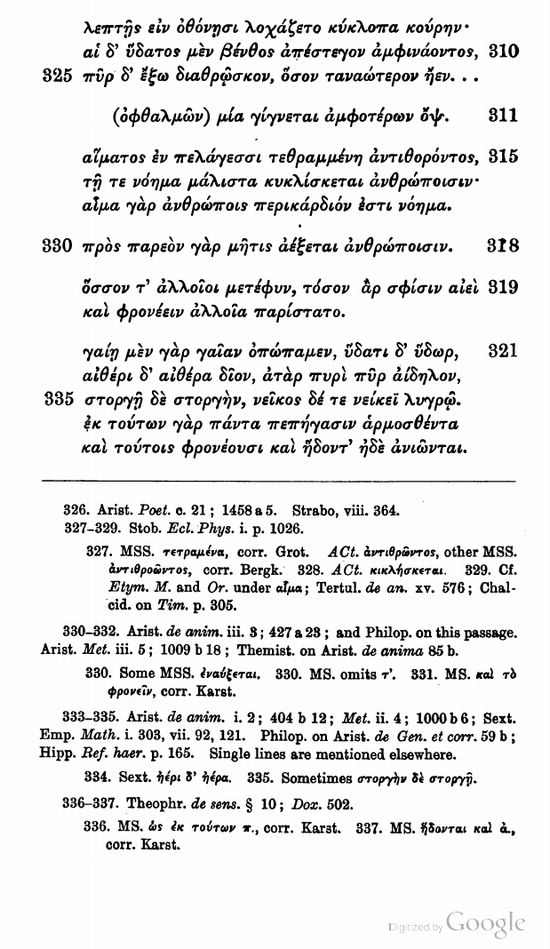

338. Would that in behalf of perishable beings thou, immortal Muse, mightest take thought at all for our thought to come by reason of our cares! Hear me now and be present again by my side, Kalliopeia, as I utter noble discourse about the blessed gods.

342. Blessed is he who has acquired a wealth of divine wisdom, but miserable he in whom there rests a dim opinion concerning the gods.

344. It is not possible to draw near (to god) even with the eyes, or to take hold of him with our hands, which in truth is the best highway of persuasion into the mind of man; for he has no human head fitted to a body, nor do two shoots branch out from the trunk, nor has he feet, nor swift legs, nor hairy parts, but he is sacred and ineffable mind alone, darting through the whole world with swift thoughts.

[Page 202]

[Page 203]

352. 0 friends, ye who inhabit the great city of sacred Akragas up to the acropolis, whose care is good deeds, who harbour strangers deserving of respect, who know not how to do baseness, hail! I go about among you an immortal god, no longer a mortal, honoured by all, as is fitting, crowned with fillets and luxuriant garlands. With these on my head, so soon as I come to flourishing cities I am reverenced by men and by women; and they follow after me in countless numbers, inquiring of me what is the way to gain, some in want of oracles, others of help in diseases, long time in truth pierced with grievous pains, they seek to hear from me keen-edged account of all sorts of things.

364. But why do I lay weight on these things, as though I were doing some great thing, if I be superior to mortal, perishing men?

[Page 204]

[Page 205]

366. Friends, I know indeed when truth lies in the discourses that I utter; but truly the entrance of assurance into the mind of man is difficult and hindered by jealousy.

369. There is an utterance of Necessity, an ancient decree of the gods, eternal, sealed fast with broad oaths whenever any one defiles his body sinfully with bloody gore or perjures himself in regard to wrong-doing, one of those spirits who are heir to long life, thrice ten thousand seasons shall he wander apart from the blessed, being born meantime in all sorts of mortal forms, changing one bitter path of life for another. For mighty Air pursues him Seaward, and Sea spews him forth on the threshold of Earth, and Earth casts him into the rays of the unwearying Sun, and Sun into the eddies of Air; one receives him from the other, and all hate him. One of these now am I too, a fugitive from the gods and a wanderer, at the mercy of raging Strife.

[Page 206]

[Page 207]

383. For before this I was born once a boy, and a maiden, and a plant, and a bird, and a darting fish in the sea. 385. And I wept and shrieked on beholding the unwonted land where are Murder and Wrath, and other species of Fates, and wasting diseases, and putrefaction and fluxes.

388. In darkness they roam over the meadow of Ate.

389. Deprived of life.

390. From what honour and how great a degree of blessedness have I fallen here on the earth to consort with mortal beings!

392. We enter beneath this over-roofed cave.

393. Where were Chthonie and far-seeing Heliope (i.e. Earth and Sun?), bloody Contention and Harmony of sedate face, Beauty and Ugliness, Speed and Loitering, lovely Truth and dark-eyed Obscurity, Birth and Death, and Sleep and Waking, Motion and Stability, many-crowned Greatness and Lowness, and Silence and Voice.

[Page 208]

[Page 209]

400. Alas, ye wretched, ye unblessed race of mortal beings, of what strifes and of what groans were ye born!

402. She wraps about them a strange garment of flesh.

403. Man-surrounding earth.

404. For from being living he made them assume the form of death by a change. . . .

405. Nor had they any god Ares, nor Kydoimos (Uproar), nor king Zeus, nor Kronos, nor Poseidon, but queen Kypris. Her they worshipped with hallowed offerings, with painted figures, and perfumes of skilfully made odour, and sacrifices of unmixed myrrh and fragrant frankincense, casting on the ground libations from tawny bees. And her altar was not moistened with pure blood of bulls, but it was the greatest defilement among men, to deprive animals of life and to eat their goodly bodies.

[Page 210]

[Page 211]

415. And there was among them a man of unusual knowledge, and master especially of all sorts of wise deeds, who in truth possessed greatest wealth of mind; for whenever he reached out with all his mind, easily he beheld each one of all the things that are, even for ten and twenty generations of men.

421. For all were gentle and obedient toward men, both animals and birds, and they burned with kindly love; and trees grew with leaves and fruit ever on them, burdened with abundant fruit all the year.

425. This is not lawful for some and unlawful for others, but what is lawful for all extends on continuously through the wide-ruling air and the boundless light.

427. Will ye not cease from evil slaughter? See ye not that ye are devouring each other in heedlessness of mind?

[Page 212]

[Page 213]

430. A father takes up his dear son who has changed his form and slays him with a prayer, so great is his folly! They are borne along beseeching the sacrificer; but he does not hear their cries of reproach, but slays them and makes ready the evil feast. Then in the same manner son takes father and daughters their mother, and devour the dear flesh when they have deprived them of life.

436. Alas that no ruthless day destroyed me before I devised base deeds of devouring with the lips!

438. Among beasts they become lions haunting the mountains, whose couch is the ground, and among fair-foliaged trees they become laurels.

440. Refrain entirely from laurel leaves.

441. Miserable men, wholly miserable, restrain your hands from beans.

442. Compounding the water from five springs in unyielding brass, cleanse the hands.

444. Fast from evil.

445. Accordingly ye are frantic with evil hard to bear, nor ever shall ye ease your soul from bitter woes.

447. But at last are they prophets and hymn-writers and physicians and chieftains among men dwelling on the earth; and from this they grow to be gods, receiving the greatest honours, sharing the same hearth with the other immortals, their table companions, free from human woes, beyond the power of death and harm.

[Page 214]

Phaed. 96 B. Is blood that with which we think, or air, or fire . . . ?1

Gorg. 493 A. And perhaps we really are dead, as I once before heard one of the wise men say: that now we are dead, and the body our tomb, and that that part of the soul, it so happens, in which desires are, is open to persuasion and moves upward and downward. And indeed a clever man—perhaps some inhabitant of Sicily or Italy—speaking allegorically, and taking the word from 'credible' (πιθανος) and 'persuadable' (πιστικος), called it a jar (πιθος). And those without intelligence he called uninitiated, and that part of the soul of the uninitiated where the desires are, he called its intemperateness, and said it was not watertight, as a jar might be pierced with holes—using the simile because of its insatiate desires.

Meno. 76 C. Do you say, with Empedokles, that there are certain effluences from things?—Certainly.

And pores, into which and through which the effluences go?—Yes indeed.

1. Cf. Cicero, Tusc. I. 9; 'Empedocles animum esse censet cordi suffusum sanguinem.'

[Page 215]

And that some of the effluences match certain of the pores, and others are smaller or larger?—It is true.

And there is such a thing as vision?—Yes.

And . . . colour is the effluence of forms in agreement with vision and perceptible by that sense?—It is.

Sophist. 24 D. And certain Ionian and Sicilian Muses agreed later that it is safest to weave together both opinions and to say that Being is many and one [πολλα τε και εν], and that it is controlled by hate and love. Borne apart it is always borne together, say the more severe of the Muses. But the gentler concede that these things are always thus, and they say, in part, that sometimes all is one and rendered loving by Aphrodite, while at other times it is many and at enmity with itself by reason of a sort of strife.

Phys. i. 3; 187 a 20. And others say that the opposites existing in the unity are separated out of it, as Anaximandros says, and as those say who hold that things are both one and many, as Empedokles and Anaxagoras.

i. 4; 188 a 18. But it is better to assume elements fewer in number and limited, as Empedokles does.

ii. 4; 196 a 20. Empedokles says that the air is not always separated upwards, but as it happens.

viii. 1; 250 b 27. Empedokles says that things are in motion part of the time and again they are at rest; they are in motion when Love tends to make one out of many, or Strife tends to make many out of one, and in the intervening time they are at rest (Vv. 69-73).

viii. 1; 252 a 6. So it is necessary to consider this (motion) a first principle, which it seems Empedokles means in saying that of necessity Love and Strife control things and move them part of the time, and that they are at rest during the intervening time.

[Page 216]

De Caelo 279 b 14. Some say that alternately at one time there is coming into being, at another time there is perishing, and that this always continues to be the case; so say Empedokles of Agrigentum and Herakleitos of Ephesus.

ii. 1; 284 a 24. Neither can we assume that it is after this manner nor that, getting a slower motion than its own downward momentum on account of rotation, it still is preserved so long a time, as Empedokles says.

ii. 13; 295 a 15. But they seek the cause why it remains, and some say after this manner, that its breadth or size is the cause; but others, as Empedokles, that the movement of the heavens revolving in a circle and moving more slowly, hinders the motion of the earth, like water in vessels. . . .

iii. 2; 301 a 14. It is not right to make genesis take place out of what is separated and in motion. Wherefore Empedokles passes over genesis in the case of Love; for he could not put the heaven together preparing it out of parts that had been separated, and making the combination by means of Love; for the order of the elements has been established out of parts that had been separated, so that necessarily it arose out of what is one and compounded.

iii. 2; 302 a 28. Empedokles says that fire and earth and associated elements are the elements of bodies, and that all things are composed of these.

iii. 6; 305 a 1. But if separation shall in some way be stopped, either the body in which it is stopped will be indivisible, or being separable it is one that will never be divided, as Empedokles seems to mean.

iv. 2; 309 a 19. Some who deny that a void exists, do not define carefully light and heavy, as Anaxagoras and Empedokles.

[Page 217]

Gen. corr. i. 1; 314 b 7. Wherefore Empedokles speaks after this manner, saying that nothing comes into being, but there is only mixture and separation of the mixed.

i. 1; 315 a 3. Empedokles seemed both to contradict things as they appear, and to contradict himself. For at one time he says that no one of the elements arises from another, but that all other things arise from these; and at another time he brings all of nature together into one, except Strife, and says that each thing arises from the one.

i. 8; 324 b 26. Some thought that each sense impression was received through certain pores from the last and strongest agent which entered, and they say that after this manner we see and hear and perceive by all the other senses, and further that we see through air and water and transparent substances because they have pores that are invisible by reason of their littleness, and are close together in series; and the more transparent substances have more pores. Many made definite statements after this manner in regard to certain things, as did Empedokles, not only in regard to active and passive bodies, but he also says that those bodies are mingled, the pores of which agree with each other. . . .

i. 8; 325 a 34. From what is truly one multiplicity could not arise, nor yet could unity arise from what is truly manifold, for this is impossible; but as Empedokles and some others say, beings are affected through pores, so all change and all happening arises after this manner, separation and destruction taking place through the void, and in like manner growth, solid bodies coming in gradually. For it is almost necessary for Empedokles to say as Leukippos does; for there are some solid and indivisible bodies, unless pores are absolutely contiguous.

325 b 19. But as for Empedokles, it is evident that he

[Page 218]

holds to genesis and destruction as far as the elements are concerned, but how the aggregate mass of these arises and perishes, it is not evident, nor is it possible for one to say who denies that there is an element of fire, and in like manner an element of each other thing—as Plato wrote in the Timaeos.

ii. 3; 330 b 19. And some say at once that there are four elements, as Empedokles. But he combines them into two; for he sets all the rest over against fire.

ii. 6; 333 b 20. Strife then does not separate the elements, but Love separates those which in their origin are before god; and these are gods.

Meteor. 357 a 24. In like manner it would be absurd if any one, saying that the sea is the sweat of the earth, thought he was saying anything distinct and clear, as for instance Empedokles; for such a statement might perhaps be sufficient for the purposes of poetry (for the metaphor is poetical), but not at all for the knowledge of nature.

369 b 11. Some say that fire originates in the clouds; and Empedokles says that this is what is encompassed by the rays of the sun.

De anim. i. 2; 404 b 7. As many as pay careful attention to the fact that what has soul is in motion, these assume that soul is the most important source of motion; and as many as consider that it knows and perceives beings, these say that the first principle is soul, some making more than one first principle and others making one, as Empedokles says the first principle is the product of all the elements, and each of these is soul, saying (Vv. 333-335).

i. 4; 408 a 14. And in like manner it is strange that soul should be the cause of the mixture; for the mixture of the elements does not have the same cause as flesh and bone. The result then will be that there are many

[Page 219]

souls through the whole body, if all things arise out of the elements that have been mingled together; and the cause of the mixture is harmony and soul.

i. 5; 410 a 28. For it involves many perplexities to say, as Empedokles does, that each thing is known by the material elements, and like by like. . . . And it turns out that Empedokles regards god as most lacking in the power of perception; for he alone does not know one of the elements, Strife, and (hence) all perishable things; for each of these is from all (the elements).

ii. 4; 415 b 28. And Empedokles was incorrect when he went on to say that plants grew downwards with their roots together because the earth goes in this direction naturally, and that they grew upwards because fire goes in this direction.

ii. 7; 418 b 20. So it is evident that light is the presence of this (fire). And Empedokles was wrong, and any one else who may have agreed with him, in saying that the light moves and arises between earth and what surrounds the earth, though it escapes our notice.

De sens. 441 a 4. It is necessary that the water in it should have the form of a fluid that is invisible by reason of its smallness, as Empedokles says.

446 a 26. Empedokles says that the light from the sun first enters the intermediate space before it comes to vision or to the earth.

De respir. 477 a 32. Empedokles was incorrect in saying that the warmest animals having the most fire were aquatic, avoiding the excess of warmth in their nature, in order that since there was a lack of cold and wet in them, they might be preserved by their position.

Pneumat. 482 a 29. With reference to breathing some do not say what it is for, but only describe the manner in which it takes place, as Empedokles and Demokritos.

[Page 220]

484 a 38. Empedokles says that fingernails arise from sinew by hardening.

Part. anim. i. 1; 640 a 19. So Empedokles was wrong in saying that many characteristics appear in animals because it happened to be thus in their birth, as that they have such a spine because they happen to be descended from one that bent itself back. . . .

i. 1; 642 a 18. And from time to time Empedokles chances on this, guided by the truth itself, and is compelled to say that being and nature are reason, just as when he is declaring what a bone is; for he does not say it is one of the elements, nor two or three, nor all of them, but it is the reason of the mixture of these.

De Plant. i.; 815 a 16. Anaxagoras and Empedokles say that plants are moved by desire, and assert that they have perception and feel pleasure and pain. . . . Empedokles thought that sex had been mixed in them. (Note 817 a 1, 10, and 36.)

i.; 815 b 12. Empedokles et al. said that plants have intelligence and knowledge.

i.; 817 b 35. Empedokles said again that plants have their birth in an inferior world which is not perfect in its fulfilment, and that when it is fulfilled an animal is generated.

i. 3; 984 a 8. Empedokles assumes four elements, adding earth as a fourth to those that have been mentioned; for these always abide and do not come into being, but in greatness and smallness they are compounded and separated out of one and into one.

i. 3; 984 b 32. And since the opposite to the good appeared to exist in nature, and not only order and beauty but also disorder and ugliness, and the bad appeared to be more than the good and the ugly more than the beautiful, so some one else introduced Love and Strife, each the cause of one of these. For if one were to

[Page 221]

follow and make the assumption in accordance with reason and not in accordance with what Empedokles foolishly says, he will find Love to be the cause of what is good, and Strife of what is bad; so that if one were to say that Empedokles spoke after a certain manner and was the first to call the bad and the good first principles, perhaps he would speak rightly, if the good itself were the cause of all good things, and the bad of all bad things.

Met. i. 4; 915 a 21. And Empedokles makes more use of causes than Anaxagoras, but not indeed sufficiently; nor does he find in them what has been agreed upon. At any rate love for him is often a separating cause and strife a uniting cause. For whenever the all is separated into the elements by strife, fire and each of the other elements are collected into one; and again, whenever they all are brought together into one by love, parts are necessarily separated again from each thing. Empedokles moreover differed from those who went before, in that he discriminated this cause and introduced it, not making the cause of motion one, but different and opposite. Further, he first described the four elements spoken of as in the form of matter; but he did not use them as four but only as two, fire by itself, and the rest opposed to fire as being one in nature, earth and air and water.

i. 8; 989 a 20. And the same thing is true if one asserts that these are more numerous than one, as Empedokles says that matter is four substances. For it is necessary that the same peculiar results should hold good with reference to him. For we see the elements arising from each other inasmuch as fire and earth do not continue the same substance (for so it is said of them in the verses on nature); and with reference to the cause of their motion, whether it is necessary to assume one or two, we must think that he certainly did not speak either in a correct or praiseworthy manner.

[Page 222]

i. 9; 993 a 15. For the first philosophy seems to speak inarticulately in regard to all things, as though it were childish in its causes and first principle, when even Empedokles says that a bone exists by reason, that is, that it was what it was and what the essence of the matter was.

Meta. ii. 4; 1000 a 25. And Empedokles who, one might think, spoke most consistently, even he had the same experience, for he asserts that a certain first principle, Strife, is the cause of destruction; but one might think none the less that even this causes generation out of the unity; for all other things are from this as their source, except god.

Meta. ii. 4; 1000 a 32. And apart from these verses (vv. 104-107) it would be evident, for if strife were not existing in things, all would be one, as he says; for when they come together, strife comes to a stand last of all. Wherefore it results that for him the most blessed God has less intelligence than other beings; for he does not know all the elements; for he does not have strife, and knowledge of the like is by the like.

Meta. ii. 4; 1000 b 16. He does not make clear any cause of necessity. But, nevertheless, he says thus much alone consistently, for he does not make some beings perishable and others imperishable, but he makes all perishable except the elements. And the problem now under discussion is why some things exist and others do not, if they are from the same (elements).

Meta. xi. 10; 1075 b 2. And Empedokles speaks in a manner, for he makes friendship the good. And this is the first principle, both as the moving cause, for it brings things together; and as matter, for it is part of the mixture.

Ethic. vii. 5; 1147 b 12. He has the power to speak

[Page 223]

but not to understand, as a drunken man repeating verses of Empedokles.

Ethic. viii. 2; 1155 b 7. Others, including Empedokles, say the opposite, that the like seeks the like.

Moral. ii. 11; 1208 b 11. And he says that when a dog was accustomed always to sleep on the same tile, Empedokles was asked why the dog always sleeps on the same tile, and he answered that the dog had some likeness to the tile, so that the likeness is the reason for its frequenting it.

Poet. 1; 1447 b 16. Homer and Empedokles have nothing in common but the metre, so that the former should be called a poet, the latter should rather be called a student of nature.

Fr. 65; Diog. Laer. viii. 57. Aristotle, in the Sophist, says that Empedokles first discovered rhetoric and Zeon dialectic.

Fr. 66; Diog. Laer. viii. 63. Aristotle says that (Empedokles) became free and estranged from every form of rule, if indeed he refused the royal power that was granted to him, as Xanthos says in his account of him, evidently much preferring his simplicity

Aet. Plac. i. 3; Dox. 287. Empedokles of Akragas, son of Meton, says that there are four elements, fire, air, water, earth; and two dynamic first principles, love and strife; one of these tends to unite, the other to separate. And he speaks as follows:—Hear first the four roots of all things, bright Zeus and life-bearing Hera and Aidoneus, and Nestis, who moistens the springs of men with her tears. Now by Zeus he means the seething and the aether, by life-bearing Hera the moist air,

[Page 224]

and by Aidoneus the earth; and by Nestis, spring of men, he means as it were moist seed and water. i. 4; 291. Empedokles: The universe is one; not however that the universe is the all, but some little part of the all, and the rest is matter. i. 7; 303. And he holds that the one is necessity, and that its matter consists of the four elements, and its forms are strife and love. And he calls the elements gods, and the mixture of these the universe. And its uniformity will be resolved into them;1 and he thinks souls are divine, and that pure men who in a pure way have a share of them (the elements) are divine. i. 13; 312. Empedokles: Back of the four elements there are smallest particles, as it were elements before elements, homoeomeries (that is, rounded bits). i. 15; 313. Empedokles declared that colour is the harmonious agreement of vision with the pores. And there are four equivalents of the elements—white, black, red, yellow. i. 16; 315. Empedokles (and Xenokrates): The elements are composed of very small masses which are the most minute possible, and as it were elements of elements. i. 24; 320. Empedokles et al. and all who make the universe by putting together bodies of small parts, introduce combinations and separations, but not genesis and destruction absolutely; for these changes take place not in respect to quality by transformation, but in respect to quantity by putting together. i. 26; 321. Empedokles: The essence of necessity is the effective cause of the first principles and of the elements.

Act. Plac. ii. 1; Dox. 328. Empedokles: The course of the sun is the outline of the limit of the universe. ii. 4; 331. Empedokles The universe <arises and> perishes according to the alternating rule of Love and Strife. ii. 6; 334. Empedokles: The aether was first separated, and secondly fire, and then earth, from which,

1. Cf. p. 119, note 1.

[Page 225]

as it was compressed tightly by the force of its rotation, water gushed forth; and from this the air arose as vapour, and the heavens arose from the aether, the sun from the fire, and bodies on the earth were compressed out of the others. ii. 7; 336. Empedokles: Things are not in fixed position throughout the all, nor yet are the places of the elements defined, but all things partake of one another. ii. 8; 338. Empedokles: When the air gives way at the rapid motion of the sun, the north pole is bent so that the regions of the north are elevated and the regions of the south depressed in respect to the whole universe. ii. 10; 339. Empedokles: The right side is toward the summer solstice, and the left toward the winter solstice. ii. 11; 339. Empedokles: The heaven is solidified from air that is fixed in crystalline form by fire, and embraces what partakes of the nature of fire and of the nature of air in each of the hemispheres. ii. 13; 341. Empedokles: The stars are fiery bodies formed of fiery matter, which the air embracing in itself pressed forth at the first separation. 342. The fixed stars are bound up with the crystalline (vault), but the planets are set free. ii. 20; 350. Empedokles: There are two suns; the one is the archetype, fire in the one hemisphere of the universe, which has filled that hemisphere, always set facing the brightness which corresponds to itself; the other is the sun that appears, the corresponding brightness in the other hemisphere that has been filled with air mixed with heat, becoming the crystalline sun by reflection from the rounded earth, and dragged along with the motion of the fiery hemisphere; to speak briefly, the sun is the brightness corresponding to the fire that surrounds the earth. ii. 21; 351. The sun which faces the opposite brightness, is of the same size as the earth. ii. 23; 353. Empedokles: The solstices are due to the fact that the sun is hindered from moving

[Page 226]

always in a straight line by the sphere enclosing it, and by the tropic circles. ii. 24; 354. The sun is eclipsed when the moon passes before it. ii. 25; 357. Empedokles: The moon is air rolled together, cloudlike, its fixed form due to fire, so that it is a mixture. ii. 27; 358. The moon has the form of a disk. ii. 28; 358. The moon has its light from the sun. ii. 31; 362. Empedokles: The moon is twice as far from the sun as it is from the earth (?) 363. The distance across the heavens is greater than the height from earth to heaven, which is the distance of the moon from us; according to this the heaven is more spread out, because the universe is disposed in the shape of an egg.

Aet. Plac. iii. 3; Dox. 368. Empedokles: (Thunder and lightning are) the impact of light on a cloud so that the light thrusts out the air which hinders it; the extinguishing of the light and the breaking up of the cloud produces a crash, and the kindling of it produces lightning, and the thunderbolt is the sound of the lightning. iii. 8; 375. Empedokles and the Stoics: Winter comes when the air is master, being forced up by condensation; and summer when fire is master, when it is forced downwards. iii. 16; 381. The sea is the sweat of the earth, brought out by the heat of the sun on account of increased pressure.

Aet. Plac. iv. 3; Theod. v.18; Dox. 389. Empedokles: The soul is a mixture of what is air and aether in essence. iv. 5; 392. Empedokles et al.: Mind and soul are the same, so that in their opinion no animal would be absolutely devoid of reason. Theod. v. 23; 392. Empedokles et al.: The soul is imperishable. Aet. iv. 9; 396. Empedokles et al.: Sensations are deceptive. 397. Sensations arise part by part according to the symmetry of the pores, each particular object of sense being adapted to some sense (organ). iv. 13; 403. Empedokles:

[Page 227]

Vision receives impressions both by means of rays and by means of images. But more by the second method; for it receives effluences. iv. 14; 405. (Reflections from mirrors) take place by means of effluences that arise on the surface of the mirror, and they are completed by means of the fiery matter that is separated from the mirror, and that bears along the air which lies before them into which the streams flow. iv. 6; 406. Empedokles: Hearing takes place by the impact of wind on the cartilage of the ear, which, he says, is hung up inside the ear so as to swing and be struck after the manner of a bell. iv. 17; 407. Empedokles: Smell is introduced with breathings of the lungs; whenever the breathing becomes heavy, it does not join in the perception on account of roughness, as in the case of those who suffer from a flux. iv. 22; 411. Empedokles: The first breath of the animal takes place when the moisture in infants gives way, and the outside air comes to the void to enter the opening of the lungs at the side; and after this the implanted warmth at the onset from without presses out from below the airy matter, the breathing out; and at the corresponding return into the outer air it occasions a corresponding entering of the air, the breathing in. And that which now controls the blood as it goes to the surface and as it presses out the airy matter through the nostrils by its own currents on its outward passage, becomes the breathing out; and when the air runs back and enters into the fine openings that are scattered through the blood, it is the breathing in. And he mentions the instance of the clepsydra.

Aet. Plac. v. 7; 419. Empedokles: Male or female are born according to warmth and coldness; whence he records that the first males were born to the east and south from the earth, and the females to the north. v. 8; 420. Empedokles: Monstrosities are due to too much or

[Page 228]

too little seed (semen), or to disturbance of motion, or to division into several parts, or to a bending aside. v. 10; 421. Empedokles: Twins and triplets are due to excess of seed and division of it. v. 11; 422. Empedokles: Likenesses (of children to parents) are due to power of the fruitful seed, and differences occur when the warmth in the seed is dissipated.1 v. 12; 423. Empedokles: Offspring are formed according to the fancy of the woman at the time of conception; for oftentimes women fall in love with images and statues, and bring forth offspring like these. v. 14; 425. Empedokles: (Mules are not fertile) because the womb is small and low and narrow, and attached to the belly in a reverse manner, so that the seed does not go into it straight, nor would it receive the seed even if it should reach it. v. 15; 425. Empedokles: The embryo is [not] alive, but exists without breathing in the belly; and the first breath of the animal takes place at birth, when the moisture in infants gives way, and when the airy matter from without comes to the void, to enter into the openings of the lungs. v. 19; 430. Empedokles: The first generations of animals and plants were never complete, but were yoked with incongruous parts; and the second were forms of parts that belong together; and the third, of parts grown into one whole; and the fourth were no longer from like parts, as for instance from earth and water, but from elements already permeating each other; for some the food being condensed, for others the fairness of the females causing an excitement of the motion of the seed. And the classes of all the animals were separated on account of such mixings; those more adapted to the water rushed into this, others sailed up into the air as many as had the more of fiery matter, and the heavier remained on the earth, and equal portions in the mixture spoke in

1. Cf. Galen, Hist. Phil. 118; Dox. 642.

[Page 229]

the breasts of all. v. 22; 434. Empedokles: Flesh is the product of equal parts of the four elements mixed together, and sinews of double portions of fire and earth mixed together, and the claws of animals are the product of sinews chilled by contact with the air, and bones of two equal parts of water and of earth and four parts of fire mingled together. And sweat and tears come from blood as it wastes away, and flows out because it has become rarefied. v. 24; 435. Empedokles: Sleep is a moderate cooling of the warmth in the blood, death a complete cooling. v. 25; 437. Empedokles: Death is a separation of the fiery matter out of the mixture of which the man is composed; so that from this standpoint death of the body and of the soul happens together; and sleep is a separating of the fiery matter. v. 26; 438. Empedokles: Trees first of living beings sprang from the earth, before the sun was unfolded in the heavens and before day and night were separated; and by reason of the symmetry of their mixture they contain the principle of male and female; and they grow, being raised by the warmth that is in the earth, so that they are parts of the earth, just as the fetus in the belly is part of the womb; and the fruits are secretions of the water and fire in the plants; and those which lack (sufficient) moisture shed their leaves in summer when it is evaporated, but those which have more moisture keep their leaves, as in the case of the laurel and the olive and the date-palm; and differences in their juices are (due to) variations in the number of their component parts, and the differences in plants arise because they derive their homoeomeries from (the earth which) nourishes them, as in the case of grape-vines; for it is not the kind of vine which makes wine good, but the kind of soil which nurtures it. v. 26; 440: Empedokles: Animals are nurtured by the substance of what is akin to them [moisture], and

[Page 230]

they grow with the presence of warmth, and grow smaller and die when either of these is absent; and men of the present time, as compared with the first living beings, have been reduced to the size of infants (?). v. 28; 440. Empedokles: Desires arise in animals from a lack of the elements that would render each one complete, and pleasures . . .

Theophr. Phys. Opin. 3; Dox. 478. Empedokles of Agrigentum makes the material elements four: fire and air and water and earth, all of them eternal, and changing in amount and smallness by composition and separation; and the absolute first principles by which these four are set in motion, are Love and Strife; for the elements must continue to be moved in turn, at one time being brought together by Love and at another separated by Strife; so that in his view there are six first principles; for sometimes he gives the active power to Love and Strife, when he says (vv. 67-68): 'Now being all united by Love into one, now each borne apart by hatred engendered of Strife;' and again he ranks these as elements along with the four when he says (vv. 77-80): 'And at another time it separated so that there were many out of the one; fire and water and earth and boundless height of air, and baneful Strife apart from these, balancing each of them, and Love among them, their equal in length and breadth.'

Fr. 23; Dox. 495. Some say that the sea is as it were a sort of sweat from the earth; for when the earth is warmed by the sun it gives forth moisture; accordingly it is salt, for sweat is salt. Such was the opinion of Empedokles.

Theophr. de sens. 7; Dox. 500. Empedokles speaks in like manner concerning all the senses, and says that we perceive by a fitting into the pores of each sense. So they

[Page 231]

are not able to discern one another's objects, for the pores of some are too wide and of others too narrow for the object of sensation, so that some things go right through untouched, and others are unable to enter completely. And he attempts to describe what vision is; and he says that what is in the eye is fire and water, and what surrounds it is earth and air, through which light being fine enters, as the light in lanterns. Pores of fire and water are set alternately, and the fire-pores recognise white objects, the water-pores black objects; for the colours harmonise with the pores. And the colours move into vision by means of effluences. And they are not composed alike . . . and some of opposite elements; for some the fire is within and for others it is on the outside, so some animals see better in the daytime and others at night; those that have less fire see better by day, for the light inside them is balanced by the light outside them; and those that have less water see better at night, for what is lacking is made up for them. And in the opposite case the contrary is true; for those that have the more fire are dim-sighted, since the fire increasing plasters up and covers the pores of water in the daytime; and for those that have water in excess, the same thing happens at night; for the fire is covered up by the water. . . . Until in the case of some the water is separated by the outside light, and in the case of others the fire by the air; for the cure of each is its opposite. That which is composed of both in equal parts is the best tempered and most excellent vision. This, approximately, is what he says concerning vision. And hearing is the result of noises coming from outside. For when (the air) is set in motion by a sound, there is an echo within; for the hearing is as it were a bell echoing within, and the ear he calls an 'offshoot of flesh' (v. 315): and the air when it is set

[Page 232]

in motion strikes on something hard and makes an echo.1 And smell is connected with breathing, so those have the keenest smell whose breath moves most quickly; and the strongest odour arises as an effluence from fine and light bodies. But he makes no careful discrimination with reference to taste and touch separately, either how or by what means they take place, except the general statement that sensation takes place by a fitting into the pores; and pleasure is due to likenesses in the elements and in their mixture, and pain to the opposite. And he speaks similarly concerning thought and ignorance: Thinking is by what is like, and not perceiving is by what is unlike, since thought is the same thing as, or something like, sensation. For recounting how we recognise each thing by each, he said at length (vv. 336-337): Now out of those (elements) all things are fitted together and their form is fixed, and by these men think and feel pleasure and pain. So it is by blood especially that we think; for in this especially are mingled <all> the elements of things. And those in whom equal and like parts have been mixed, not too far apart, nor yet small parts, nor exceeding great, these have the most intelligence and the most accurate senses; and those who approximate to this come next; and those who have the opposite qualities are the most lacking in intelligence. And those in whom the elements are scattered and rarefied, are torpid and easily fatigued; and those in whom the elements are small and thrown close together, move so rapidly and meet with so many things that they accomplish but little by reason of the swiftness of the motion of the blood. And those in whom there is a well-tempered mixture in some one part, are wise at this point; so some are good orators, others good artisans, according as the mixture is in the

1. Reading κινουμενον with Diels.

[Page 233]

hands or in the tongue; and the same is true of the other powers.

Theophr. de sens. 59; Dox. 516. And Empedokles says of colours that white is due to fire, and black to water.

Cic. De nat. deor. xii.; Dox. 535. Empedokles, along with many other mistakes, makes his worst error in his conception of the gods. For the four beings of which he holds that all things consist, he considers divine; but it is clear that these are born and die and are devoid of all sense.

Hipp. Phil. 3; Dox. 558. And Empedokles, who lived later, said much concerning the nature of the divinities, how they live in great numbers beneath the earth and manage things there. He said that Love and Strife were the first principle of the all, and that the intelligent fire of the monad is god, and that all things are formed from fire and are resolved into fire; and the Stoics agree closely with his teaching, in that they expect a general conflagration. And he believed most fully in transmigration, for he said: 'For in truth I was born a boy and a maiden, and a plant and a bird, and a fish whose course lies in the sea.' He said that all souls went at death into all sorts of animals.

Hipp. Phil. 4; Dox. 559. See Herakleitos, p. 64.

Plut. Strom. 10; Dox. 582. Empedokles of Agrigentum: The elements are four—fire, water, aether, earth. And the cause of these is Love and Strife. From the first mixture of the elements he says that the air was separated and poured around in a circle; and after the air the fire ran off, and not having any other place to go to, it ran up from under the ice that was around the air. And there are two hemispheres moving in a circle around the earth, the one of pure fire, the other of air and a little fire mixed, which he thinks is night. And motion

[Page 234]

began as a result of the weight of the fire when it was collected. And the sun is not fire in its nature, but a reflection of fire, like that which takes place in water. And he says the moon consists of air that has been shut up by fire, for this becomes solid like hail; and its light it gets from the sun. The ruling part is not in the head or in the breast, but in the blood; wherefore in whatever part of the body the more of this is spread, in that part men excel.

Epiph. adv. Haer. iii. 19; Dox. 591. Empedokles of Agrigentum, son of Meton, regarded fire and earth and water and air as the four first elements, and he said that enmity is the first of the elements. For, he says, they were separated at first, but now they are united into one, becoming loved by each other. So in his view the first principles and powers are two, Enmity and Love, of which the one tends to bring things together and the other to separate them.

Simp. Phys. = Simplicii in Aristotelis physicarum libros qua ores edidit H. Diels, Berlin 1882.

Simp. Cael. = Simplicius, Commentary on Aristotle's De caelo.

Dox. = Diels, Doxographi Graeci, Berlin 1879.